In the beginning…

Genesis 1 is a hot potato in the debate between Science and the Bible. It all started with the sermon which Caccini, a Dominican friar, preached in Florence in 1614 against Galileo’s assertion that the earth moved round the sun: “Ye men of Galilee, why stand ye gazing up into heaven?” (Acts 1.11) But by the end of the 17th century Galileo’s assertion was common knowledge.

Many Christians still take Genesis 1 as a literal account of how the earth and the universe were created. They believe that if you deny the literal truth of Genesis 1 then the whole Bible loses its claim to be true. This is rooted in a misunderstanding. The word “Bible” comes from the Greek ’ta biblia’, which means books, plural. They were written down on separate scrolls as books were not invented till the Christian era. In other words, the Bible is a library, written by different writers over a period of a thousand years. We need to take each part on its own terms first, before trying to build an overarching structure.

So, how should we read Genesis 1?

The six days of creation

Simply look at the text. It describes the creation in six days. The seventh is God’s day of rest, when the created world gets going under its own steam. At first it seems to give a reasonably accurate chronological timescale of creation, but a second glance shows that cannot be. The way to understand it is to draw up two parallel columns and set down what was created each day. So we have:

First three days

Day 1 Light and darkness

Day 2 A firmament/dome to separate water above and below, so making space for air, i.e. organising air and water

Day 3 Land and plants

Second three days

Day 4 Sun, moon & stars

Day 5 Birds and fishes

Day 6 Animals & humans

What we have is NOT a straight chronological account. It is more like a drama, with three stage sets produced first, and then the characters to act in them. That is why the sun and moon appear on day 4, and birds and fishes on day 5. If it were published as a stand-alone book and placed in a public library it would be classified as drama or poetry, not as science.

The message of Genesis 1

But there is a positive message of Genesis1. It is that the universe is ordered. There is an orderly pattern to creation, and it behaves in an orderly way. This is how science becomes possible. General laws or rules can be established, and we expect hem to continue to operate. There is no mischief-making god or spirit who might decide on a whim to stop gravity working at a particular time and spot.

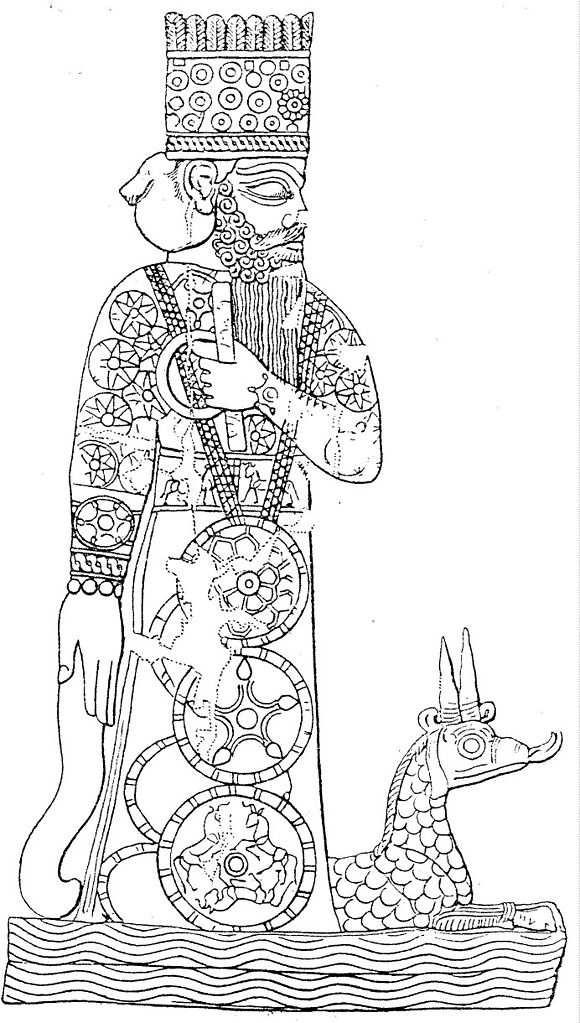

It is quite unlike the mythologies of the ancient world where the universe is essentially chaotic, the result of a battle between various gods, as in the Babylonian Creation Epic:

So they came together – Tiamat and Marduk, Sage of the gods. They advanced into conflict, they joined forces in battle… As she opened her mouth, Tiamat, to devour him, he shot there through an arrow, it tore into her womb… Thereat he strangled her, made her life-breath ebb away. He slit her in two, like a fish in the drying yards. The one half he positioned and secured as the sky. There he traced lines for the mighty gods, stars, star-groups and constellations he appointed for them…

He placed her head in position, heaped the mountains upon it, made the Euphrates and Tigris to flow through her eyes…

So they came together – Tiamat and Marduk, Sage of the gods. They advanced into conflict, they joined forces in battle… As she opened her mouth, Tiamat, to devour him, he shot there through an arrow, it tore into her womb… Thereat he strangled her, made her life-breath ebb away. He slit her in two, like a fish in the drying yards. The one half he positioned and secured as the sky. There he traced lines for the mighty gods, stars, star-groups and constellations he appointed for them…

He placed her head in position, heaped the mountains upon it, made the Euphrates and Tigris to flow through her eyes…

(Note: Tiamat is goddess of the sea and of chaos)

Science: the real challenge

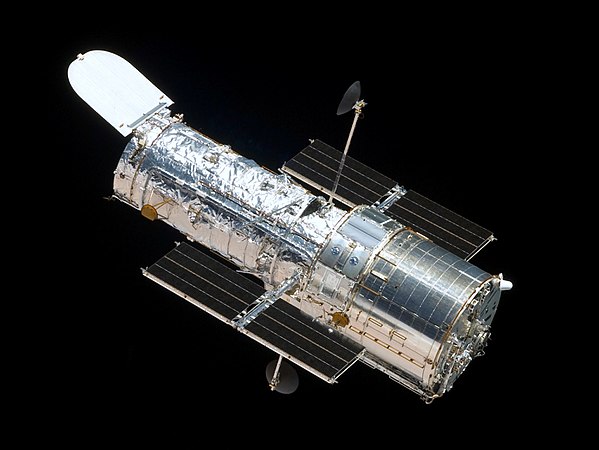

The real challenge that science makes to faith is in the religious imagination. The French philosopher Blaise Pascal (1623 – 1662) wrote, “The eternal silence of these infinite spaces terrifies me.” That was a time when the inhabited universe had shifted from the earth as a disc surrounded by sun, moon and stars, to a planet spinning around the sun along with other planets and with the stars vast distances away. Nowadays although almost all the stars we can see are in our galaxy, we know there are at least 2 trillion galaxies each with about 100 thousand million stars. And they are moving away from us into the emptiness of space at increasing speed.

“Isaac Asimov has a dramatic illustration: it is as if all the matter of the universe were a single grain of sand, set in the middle of an empty room 20 miles long, 20 miles wide and 20 miles high. Yet at the same time, it is as if that single grain of sand were pulverised into a thousand million million million fragments, for that is approximately the number of stars in the universe.” (R Dawkins, “Unweaving the Rainbow” p.118)

How old is the universe? James Ussher (1581 – 1656), Archbishop of Armagh in Ireland, worked out in 1604, using just the Bible, that the universe began on 23rd October 4004 BC. How can we believe that, when the oldest human tool, discovered in East Africa, has been dated to 2.5 million years ago.

A key discovery by Isaac Newton (1643 – 1727) was that colours are produced when you direct light through a glass prism – what the poet Keats called “unweaving the rainbow”. This was the foundation of the the work American astronomer Edwin H ubble. In 1929 he showed that light shifts towards the red end of the spectrum when objects are moving away from us. From the redshift observable in the cosmic microwave background radiation, we can calculate when everything would have been crunched together just before the Big Bang. This enabled the European Space Agency in 2013 to calculate that the universe is 13.82 billion years old. That is 13,820,000,000 years old. Unimaginable distances and time.

But essential for us. When the universe began, all that existed was hydrogen and some helium. It needed billions of years for stars and galaxies to form, grow, decay, explode in supernovae, and repeat. It was in the furnace of massive stars that elements up to iron were created; heavier elements such as uranium and gold were created in super-novae and shot out into space to become planets and ultimately us. We are composed from the ashes of dead stars.

From macro to micro

If the universe is unimaginably vast, it is also unimaginably tiny. For a start, most of us don’t exist. That is to say that of all the atoms and molecules which make up our bodies, indeed all the physical world around us, is 99.9999999% empty space. If the nucleus of an atom were as big as a peanut, the atom itself would be the size of a baseball stadium. What happens in all that empty space? Apart from neutrons and electrons there are the even tinier quarks. Quarks were postulated as far back as 1964, but it was only in 2015 that CERN (the European Centre for Nuclear Research in Switzerland) demonstrated the existence of the pentaquark – a subatomic particle with four quarks and one antiquark bound together. At an even more micro level, quarks are held together by gluons which don’t have any mass at all. So what is in that empty space? The answer seems to be wave functions and invisible quantum fields. If you can’t understand all this, don’t worry. Richard Dawkins wrote:

“Sometimes I imagine that I have some appreciation of the poetry of quantum theory, but I have yet to achieve an understanding deep enough to explain it to others. Actually, it may be that nobody really understands quantum theory… but nobody doubts its phenomenal success in predicting detailed experimental results.” (q.v. p.50)

Is our God too small?

What impact does all this mind-boggling science have on our thinking about God? Richard Dawkins has a great quote from Carl Sagan, an astronomer, astrophysicist and cosmologist who championed the search for extra-terrestial life.

“How is it that hardly any major religion has looked at science and concluded, ‘This is better than we thought! The Universe is much bigger than our prophets said, grander, more subtle, more elegant’? Instead they say, “No, no, no! My god is a little god, and I what him to stay that way.” A religion, old or new, that stressed the magnificence of the Universe as revealed by modern science might be able to draw forth reserves of reverence and awe hardly tapped by the conventional faiths.” (q.v. p.114, op. cit. ‘Pale Blue Dot’ (1995))

How does the Bible view the universe?

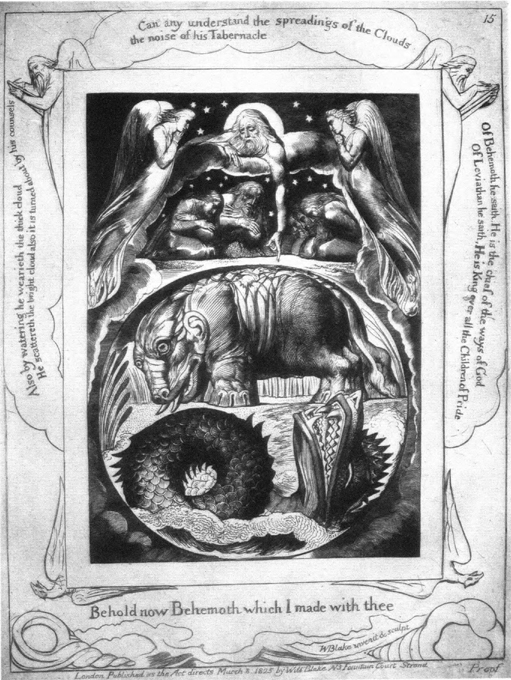

Nature documentaries are very popular, especially the ones about penguins and baby polar bears. But the reality can be much more brutal. David Attenborough says there are some things he simply will not show in his films. The great virtue of the Bible is that it does not gloss over the uncomfortable or painful parts of creation. On the fifth day of creation God is said to have created the great sea-monsters, fearsome beasts for which the land-locked Israelites had no use. Psalms 104 is the great psalm of creation. The Psalmist celebrates light, sky, clouds, winds, oceans, mountains, wild animals, birds, grass, bread, oil and wine, cedars, storks, wild goats, coneys (i.e. hyraxes), young lions, creeping sea-creatures and Leviathan, the whole lot. In Romans 1.20 St Paul is certain that the universe points towards God, but it is to “his eternal power and divine nature, invisible though they are” that creation points, not to other characteristics such as loving-kindness and faithfulness.

The key Biblical passage is chapters 38 and 39 of the Book of Job. Job is a righteous man (not an Israelite) who suffers a whole series of disasters – death of all his children, loss of all his possessions and finally an excruciating disease. It is so bad that he simply prays for death, and blames God for creating such a dysfunctional world. Finally God shows up, answering Job “out of the whirlwind”. The Lord does not attempt to answer Job’s accusations. He simply points to the amazingness of the universe:

“Were you there when I laid the foundations of the earth? …

“Can you bind the chains of the Pleiades? …

“Do you know when the mountain goats give birth? …

“Is the wild ox willing to serve you? …

“Is it by your wisdom that the hawk soars? … Its young ones suck up blood; and where the slain are, there it is.”

In other words, he effectively tells Job to know his place. This does not seem kind or loving, but it is similar to the experience of some people when that have a surprise encounter with God. Frances Young (1939 to date) is a theologian who had a severely disabled son as her firstborn. It made life incredibly difficult and distressing. Where was God in all this?

“I know precisely what chair I was sitting in, and that I was sitting on the edge of the chair, about to go off and do something or other around the house. It was one of those ‘thought-flashes’ that seem to have no context: “It doesn’t make any difference to me whether you believe in my reality or not.”

I had a sense of being stunned, of being put in my place. It is difficult to see why, really. It is after all a theological commonplace, and I do not think that I had thought for a very long time that my intellect could solve the problems. It was all so very ordinary, too. Nothing dramatic happened. I got up and got on with whatever I was going to do. I have not, however, seriously doubted the reality of God since that moment.”

(from ‘Face to Face’ p.64, quoted in ‘Job for Public Performance’)

For further reading:

Richard Dawkins – Unweaving the Rainbow

Arthur Koestler – The Sleepwalkers (Copernicus, Galileo, Kepler & Newton)

Andy Roland – The Book of Job for Public Performance

© Andrew Roland 2019