WHEN IS A BOOK NOT A BOOK?

One possible answer is, when you need an electron microscope to read it, like the Nano Bible in which all 1.2 million letters have been etched on to a disc the size of the tip of a pen. (I saw it in the Israel Museum in 2017).

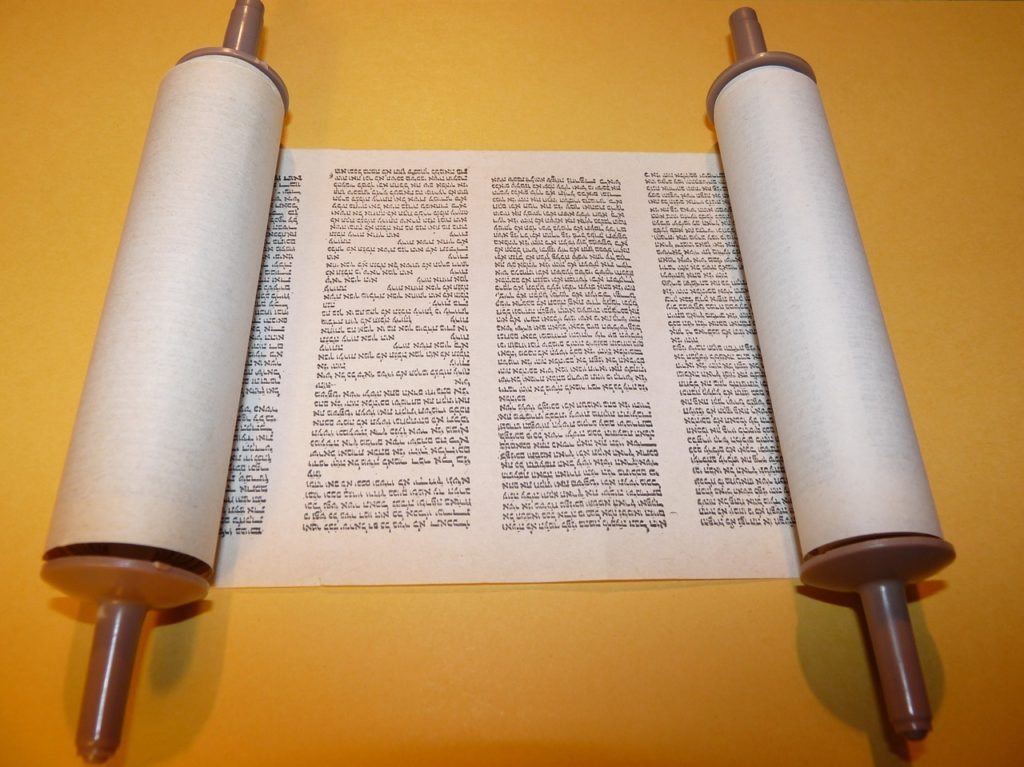

Another answer is, when you don’t need a large wheelbarrow to carry it round, a bit like the 32 volumes of the 9th edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica. But that is just what the Bible originally was like. A collection of very large scrolls, which if you wanted to hide, would have to be put in large pottery jars and stored in several caves, like the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Yet another answer is that it is an anthology. This one was assembled over the course of a thousand years, written in two different languages and created three religions. The actual word ‘Bible’ comes from the Greek, ‘Biblia’ – books, plural. And the books referred to are not just two, ‘Old Testament’ and ‘New Testament’. They are 66, if you look up the index.

Except, they’re not 66. Each of the books in the index may have had more than one author, and gone through a period of development. So, for instance, Isaiah consists of two sections separated by 150 years. On the other hand, the four books of 1 & 2 Samuel and 1& 2 Kings (or in Catholic Bibles 1, 2, 3 &4 Kings) is actually one long uninterrupted history covering over 400 years. Today it would be a single volume called perhaps ‘The Two Kingdoms – a History’. In the New Testament three ‘books’ don’t deserve the title at all. They are Paul’s personal letter to Philemon about a runaway slave, and 2 & 3 John. Today each one would be an email.

So – how many books are there in “the Books’? The best answer is, quite a lot.

PROBLEMS WITH THE OLD TESTAMENT

It’s a common view that Christians can do without the Old Testament, that the God of the Old Testament is an angry and punishing God, while the God of the New Testament is a God of love. This is a misconception. There is plenty of God passionately loving his people in the Old Testament, and quite a bit of God’s anger and judgement in the New.

Two big issues do stand out. One is the Law, in Hebrew the Torah, the whole bundle of religious, social and ethical regulations which defined Jewish life. The Early Church decided that the coming of the Holy Spirit had superseded the Law for God’s new community, (Acts 15.19-21). The other is the sheer bloodthirstiness of the early histories and God’s explicit command for Israel to wipe out whole populations. No wonder that the early Christian theologian Marcion (85 – 160) decided that the Church should abandon all the Old Testament, as well as much of the New Testament apart from the letters of Paul and most of Luke, (though he had to censor that as well). The trouble is that the Christian faith grew out of the Jewish religion. As Albert Schweizer (1875-1965) famously said, “Jesus was not a Christian, he was a Jew.” However, when this aspect of the Bible is used to justify the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians from their native land – 750,000 were made refugees in 1948 – this becomes a very hot potato indeed. Palestinian theologians like Naim Ateek are clear that the whole of the Bible has to be judged through the teaching and example of Yeshua ben Yosef – ‘Jesus’ in Greek.

LET’S ABANDON “THE OLD TESTAMENT”

But what about the phrase ‘the Old Testament’. ‘Testament’ is an old-fashioned word for ‘covenant’. It comes from a phrase in Paul’s second letter to the Corinthians. “to this very day when they hear the words of the old covenant, that same veil is still there …” (2 Corinthians 3.14) My father was Jewish and I always experience the phrase as quite insulting. The synagogue refers to the Hebrew scriptures as the ‘Tenakh’, referring to the three parts of their holy book; ‘Te’ for Torah or Law, the first five books of the Bible from Genesis to Deuteronomy; ‘Na’ stands for Nevi’im or Prophets; these are divided into the Early Prophets, which means all the historical books, and the Later Prophets, from Isaiah onwards; and ‘K’ stands for K’tuvim meaning Writings, i.e the Psalms and the wisdom books like Proverbs and Job.

I suppose an obvious question is, what did Jesus call ‘the Old Testament’? Answer: He called it ‘the law and the prophets’. “In everything do to others as you would have them do to you; for this is the law and the prophets.” (Matthew 7.12) I guess that he included the Psalms under the heading of ‘prophets’, as they were seen as prayers of David. Even Paul used the phrase: “The righteousness of God has been disclosed, and is attested by the law and the prophets.” (Romans 3.21)

If it was good enough for Jesus and Paul, shouldn’t it be good enough for us?

WHO DECIDED ON WHAT TO PUT IN THE LAW AND THE PROPHETS?

It used to be thought that the Hebrew Scriptures were defined at the Council of Jamnia or Yavneh around 90 AD, a theory put out by Heinrich Graetz in 1871. Few scholars now accept this, or indeed that a Council of Jamnia ever took place. There were simply ongoing debates among different schools of rabbis as to whether the Books of Chronicles, Ecclesiastes and Song of Songs should be included in the list of authoritative and sacred writings, i.e. whether they ”defiled the hands”or not. (Meaning that you had to wash your hand after touching the holy scriptures before handling common objects).

It was probably the scribes, both in Babylon and returning from exile in the 5th century BCE, who copied out the books they regarded as sacred scripture. Others were included over the centuries, perhaps Ruth and Jonah. Josephus, writing in about 95 AD said, ”We have not an innumerable multitude of books among us, disagreeing from and contradicting one another (as the Greeks have), but only twenty-two books, which contain all the records of all the past times; which are justly believed to be divine; and of them five belong to Moses, which contain his laws and the traditions of the origin of mankind till his death… the prophets, who were after Moses, wrote down what was done in their times in thirteen books. The remaining four books contain hymns to God, and precepts for the conduct of human life.” (Against Apion, book 1)

If we count the four historical books as one, together with the twelve minor prophets, and excluding Chronicles we have exactly the same number as Josephus.

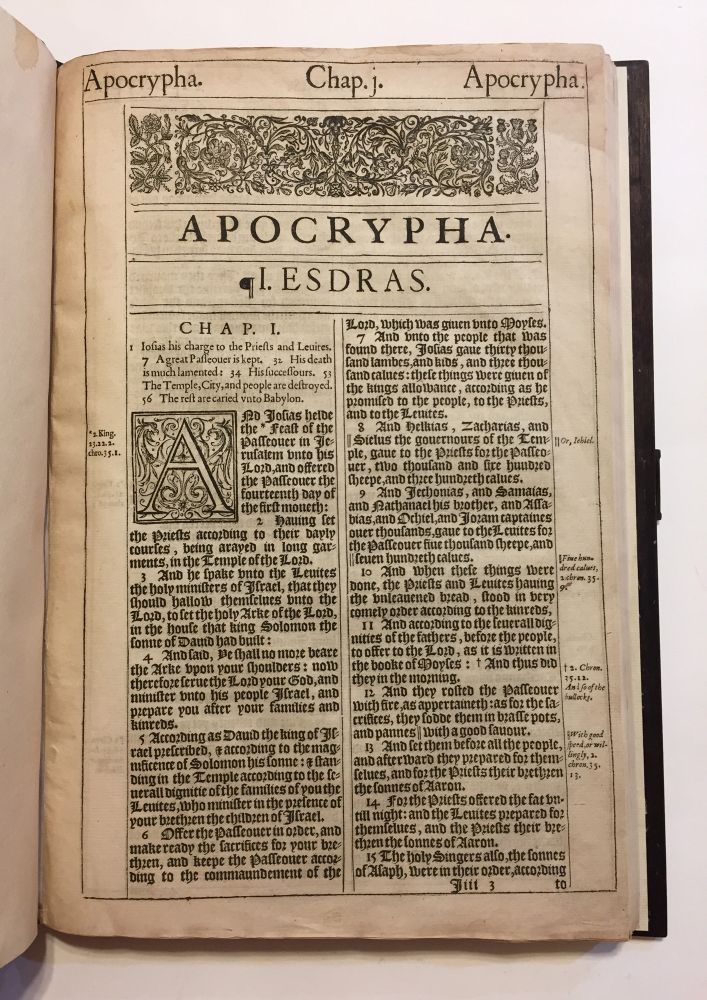

WHAT’S THE APOCRYPHA?

‘Apocrypha’ means ‘hidden’, which is a bit of a misnomer because there is nothing hidden about them. It simply means useful Jewish writings coming out of the world of Hellenistic (Greek-speaking) Judaism. They were popular and were adopted by the early Church, and are still included in Roman Catholic and Orthodox Bibles, using the order of books in the Septuagint, Greek, translation (3rd century BCE). Luther, the Protestant Reformer, put these Greek Jewish writings into a separate appendix in 1534. He hoped that this would encourage the Jews of Europe to convert to the Christian faith. It didn’t work. But the Apocrypha continued to be printed as part of most Protestant Bibles until 1826, when the British and Foreign Bible Society, pressured by the Scottish Presbyterians, refused to pay for printing Bibles which included the Apocrypha. (Encyclopaedia of Protestantism vol 4. p.395)

The Apocrypha is extremely valuable; Maccabees 1 is a contemporary account of the Maccabean Revolt, 167 BCE, a crucial event in the history of Israel. Without the Maccabees, Galilee, where jesus grew up, would have remained Gentile, which is what the name means: “galil hagoyim = region of the gentiles. Ecclesiasticus (or ben Sirach) and the Wisdom of Solomon, are 2nd century BCE motivational books similar to Proverbs. These show the context which Jesus grew up in. Extracts can be found in my book ‘Bible in Brief’.

WHO DECIDED ON WHAT TO PUT IN THE NEW TESTAMENT?

In Flanders’ and Swann’s ‘Song of Patriotic Prejudice’ (1963), one of the criticisms of the Scotchman is “he doesn’t have bishops to show him the way.” Not true when it comes to the Bible. It was the bishops who eventually decided on what the New Testament should include. But large meetings of bishops was impossible while Christianity was still illegal as it was up to 315. Our Bible was officially approved at a synod in Rome in 382. That only ratified conventions that had had been accepted for 200 years. A papyrus fragment, probably from about 170 AD, lists the four gospels, Acts, Paul’s letters, Jude and John. Only Hebrews, James and Peter are not mentioned. Writing about 180, Irenaeus cites the whole of our New Testament apart from Philemon, 2 Peter and 3 John. So our canon of Scripture was effectively fixed within 150 years of death of Jesus.

The only exception is the Revelation of John which is still not used in public worship in the Orthodox churches.

What was the basis of their decision? The Muratorian fragment tells us:

‘Hermas wrote The Shepherd “most recently in our time”, in the city of Rome, while bishop Pius, his brother (d. 155), was occupying the chair of the church of the city of Rome. And therefore it ought indeed to be read; but it cannot be read publicly to the people in church either among the Prophets, whose number is complete, or among the Apostles, for it is after their time.’

In other words, the criterion was simply, Were they there? If something was written after the first apostles, such as the letters of Clement (c. 96) or Ignatius (c.110) or the Didache (probably about 100) or Hermas (c.150), then however spiritually useful they were, they were not included.

WHAT ABOUT THE LOST GOSPELS?

Various writings called gospels were discovered in the last century such as the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Philip and the Gospel of James. The secular establishment tends to see them as great new discoveries which discredit the actual gospels, such as in Dan Brown’s “The Da Vinci Code” and even the BBC KS3 resource for Religious Studies. They all seem to be written at least a hundred years after the Gospels in the Bible, and more importantly are designed for those who see themselves as a spiritual elite with a knowledge, ‘gnosis’, which sets them apart from the rest of the human race. I have written a separate blog in which you can read for yourselves extracts from the gospels of Thomas, Philip etc. It will come out next week on my website bibleinbrief.org.

TO SUM UP

The Bible has good credentials. It was collected by people who wanted to hand their traditions on faithfully. But it does not mean that we have to believe that because it’s in the Bible it must be true. It is reasonable to ask questions like, who wrote this, how near the events was it written? Was there another angle which appears elsewhere or has not been passed on? All these questions and more will be explored in the rest of this book, with the hope that they can help us in making sense of the Bible.

NOW READ ON…

An easy way to explore the Bible as a whole is to use my book, Bible in Brief. Graham Tomlin, Bishop of Kensington, said, “This book does what few others do – it offers a very helpful guide for those looking for a brief overview of the Bible and its story.”

Each day there is an (undated) passage to read, and a question which you can respond to on the opposite page. It has pictures, maps, timelines, introductions, and ‘The Other Side”: quotes from the surrounding cultures, including the Apocrypha. Look inside it at ‘bibleinbrief.org’. Buy it there and it will be sent p&p free!