THE LANGUAGES OF THE BIBLE

The Bible was written 1,500 years before English even existed as a language. The two major languages in which the Bible is written were Hebrew and Greek, plus occasionally Aramaic.So, unless we want to study for years, we have to make do with translations. These can be word-for-word translations which may be accurate but incomprehensible, like the 1611 version of Paul’s letters. Modern paraphrases which can be just bizarre. One of my favourites is the verse Ecclesiastes 9.8, which in the NRSV reads: “Let your garments always be white; do not let oil be lacking on your head”

This, in the Living Bible, becomes: “Always wear fine clothes, with a dash of Cologne.”

We can’t necessarily learn the languages, but we can learn to appreciate the task of translation.

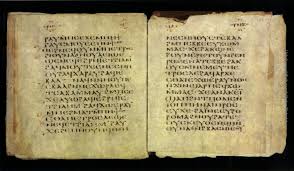

Hebrew

Almost all the Old Testament (or ‘the Law and the Prophets’, as Jesus called it) was written in Hebrew. Most of its words are built up of three consonants, whose meaning can change depending on what vowels you put in, because they are not written down.

A classic case is ‘Jehovah’, which is made up of the consonants ‘YHWH’. So should it be pronounced ‘Jehovah’ or ‘Yahweh’? If you are reading a Bible with footnotes, it is always worth checking up for variant readings at the bottom of the page.

Following J B Phillips’ success in translating the New Testament into modern English, in 1963 he published his translation of the four oldest prophets, Isaiah, Hosea, Amos and Micah. In his preface he wrote:

Who could feel at home in the presence of the monolithic grandeur of Old Testament Hebrew? … There seems to be no concession to human frailty of understanding in these terse, craggy characters. Message after message is packed full of power, and expressed in a terrifying economy of words. … Martin Luther (1483 – 1546) … wrote, “The words of the Hebrew tongue have a peculiar energy. It is impossible to convey so much so briefly in any other language.” (Four Prophets, p.viii)

Greek

The New Testament was written in Greek, the ‘lingua franca ‘ of the ancient world. It became the language of the Persian Empire after its conquest by Alexander the Great, and of the Roman empire as it conquered the whole of the Mediterranean, including Egypt. In 100 AD the Roman satirist Juvenal scornfully called Rome “Graeca urbs” – “the Greek city”. It was a simplified variant of classical Greek, e.g. in having no ‘Middle voice’ between Active and Passive, but absolutely understandable throughout the known world.

This was before the New Testament came to be written. By 300 BC the very large Jewish colony in Alexandria, Egypt, could no longer understand Hebrew, so the Old Testament was translated into Greek, known as the Septuagint or LXX. (This term enshrines the story that seventy Jewish scholars translated it independently into Greek, and when they compared versions, they were all the same!) It was this translation that was used by the writers of the New Testament and the Early Church, right up to 405 when Jerome finished translating the Old Testament from the Hebrew.

Up to that point Christians did not distinguish between Old Testament books which were written in Hebrew from ones written in Greek. These later books, comprising history, legends and wisdom, were written close to Jesus’ lifetime. It was only In 1536 thatMartin Luther placed them in a separate section called the Apocrypha.

J B Phillips had hoped that the LXX could help him with his translation, but no.

For the most part I found their Greek perfectly clear and intelligible, but it was baffling and disquieting to find that, when faced with a real difficulty in the Hebrew, the Greek version provided me with something either quite different or else – and I hate to say this – with a slick pious phrase. (Four Prophets p. viii)

But the Septuagint did give the New Testament writers the linguistic tools that they needed. In ordinary ‘koine’ Greek there was little use of words like brother, fellowship, apostle, saviour, preach, and, famously, agape/love. These are some of the gifts that the Septuagint has given to the New Testament and the Church.

I find that the little Greek I learned for my theology invaluable for checking up on translators’ quirks, and there are plenty of helps available, particularly the Interlinear New Testament, which translates each word underneath the Greek, while giving a standard translation in the margin.

Aramaic

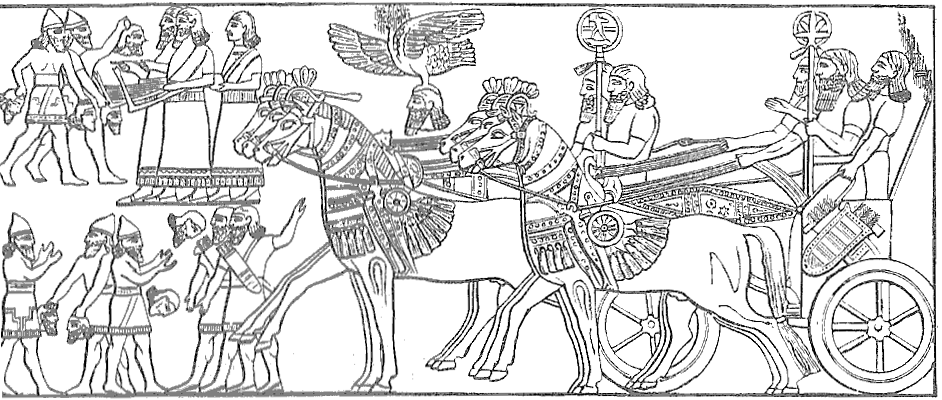

Finally, there is Aramaic, the language of the Syrian tribes, which became the standard international language of the Middle East for centuries. In 600 B.C. an Assyrian army laid siege to Jerusalem, and the Assyrian general made a speech:

Thus says the great king, the king of Assyria: On what do you base this confidence of yours? Do you think that mere words are strategy and power for war? On whom do you now rely, that you have rebelled against me? …

Then Eliakim, Shebnah, and Joah said to the Rabshakeh, ‘Please speak to your servants in the Aramaic language, for we understand it; do not speak to us in the language of Judah within the hearing of the people who are on the wall.’ But the Rabshakeh said to them, ‘Has my master sent me to speak these words to your master and to you, and not to the people sitting on the wall, who are doomed with you to eat their own dung and to drink their own urine?’ … Then he called out in a loud voice in the language of Judah, ‘Hear the word of the great king, the king of Assyria! Thus says the king: “Do not let Hezekiah deceive you, for he will not be able to deliver you out of my hand…. (2 Kings 19.19 – 29, ed.)

There are two longish passages in the Old Testament which are in Aramaic. Three chapters in Ezra (4.8 – 6.18 and 7.12-26) give verbatim correspondence to and from the Persian kings Artaxerxes and Darius. The other is six chapters in Daniel, (2.4 – 7.28) from Daniel’s interpretation of Nebuchadnezzar’s dream to his dream of the four supernatural beasts/empires. Daniel has been dated variously to 550 BC and 160 BC. Do the Aramaic passages give a clue as to when Daniel was written? Or not?

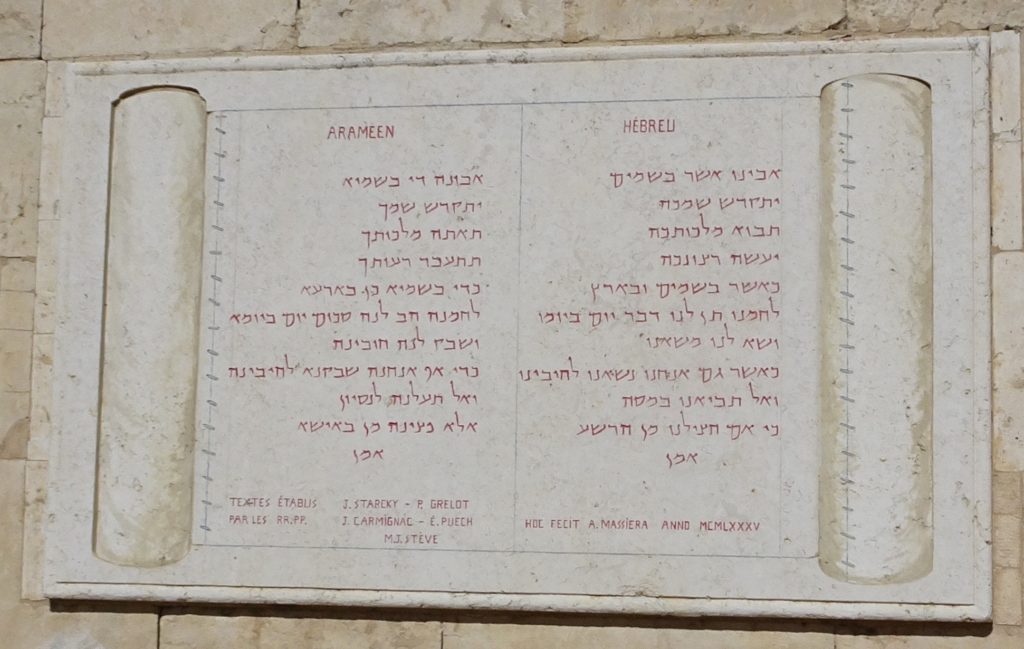

Finally, Aramaic was the language that Jesus and most Palestinian Jews spoke as their first language. We have some of Jesus actual words recorded in Mark. “Abba”- Father, or Dad (14.36); :”Talitha koum” – ‘Little girl, get up’ (5.41); “Ephphatha” – be opened (7.34); and most famously, “Eloi, Eloi, lama sabachthani?” – My God, my God, why have you forsaken me? (14.34). Some scholars have tried translating Jesus’ words back into Aramaic, such as the Lord’s Prayer, with interesting results.

My guess is that most Jews in Palestine were bilingual in Aramaic and Greek. What language did Peter address the crowd on the day of Pentecost? If the strangers from Rome, with Cretans and Arabs could understand Aramaic, that would have been a miracle!

New Testament Names

Some of the names in the New Testament illustrate the tension between Aramaic and Greek. The lady whom Peter brought back from death in Acts 9.36-41 was called Tabitha, Dorcas in Greek, both meaning gazelle. And Peter (the Rock) himself was not called that by Paul, nor presumably by any of his friends. He was called “Kephas” – the Aramaic word for rock (1 Corinthians 15.5, Galatians 1.18).

But the biggest problem comes because Greeks had no way of speaking or writing the sound ‘sh’, and they instinctively added ‘-us’ or ‘os’ on the end of names so they could put the right case endings on. So Jesus was never called Jesus by his family and friends. He was always ‘Yeshua’ – our equivalent to ‘Joshua’ or ‘Jo’. The same change happens in the Septuagint, so it comes as a bit of a shock when reading that, to learn that it was Jesus who won the battle of Jericho! Why don’t we start using Jesus’ actual name in our worship: “Yeshua (God saves). Yesh you are!”