Between now and Easter (4th April) I will be writing a series of weekly blogs on Jesus’ last eight days as he travels from Jericho, to the Temple in Jerusalem, through his confrontations with the authorities and his arrest and death, up to the resurrection.

It is told in greater detail in my book ‘Jesus the Troublemaker – his last 8 days.’

Today I look at the all-day journey to Jerusalem and the questions that arise.

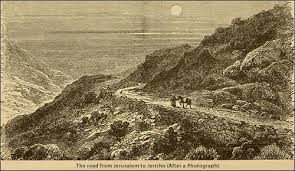

THE WALK FROM JERICHO

From Jericho to Jerusalem is an 18 mile trek uphill, dry, rocky, with no water available for most of it. It is barely mentioned by the gospel writers, whose attention is focused on the public entry into Jerusalem. But it was a full day. What do we know about it?

Only Luke supplies any details. In fact he records two significant speeches, one on the way walking uphill, the other when Jesus comes in sight of the Temple and the city. Both are dramatic and unhappy.

Matthew’s story

The first is the story about a nobleman going away and giving his servants some money to trade with. It is a story which Matthew clearly uses as the basis of the later parable of the talents (Matthew 25.14-30).

In Matthew’s version, told just before Passover and the Last Supper, a man is going on a journey, and he gives three servants five, two and one talent respectively to make money with. (A talent of silver was a unit of weight, worth about £1 million). The first two made 100% profit. The third squirrelled his talent away and got the sack as a result. Moral: don’t be idle!

Luke’s story

Luke’s version (Luke 19.1-27) is very strange. There is no parable or story by Jesus anything like it. It is actually history.

‘“A nobleman went to a distant country to get royal power for himself and then return. But the citizens of his country hated him and sent a delegation after him, saying, “We do not want this man to rule over us.”’

This is exactly what happened around the time of Jesus’ birth. Herod I died in 4 BC and his son Archelaus went to Rome to have Herod’s last will confirmed by the Roman emperor Augustus and be appointed as Rome’s client king. In my book I spell out the historical background to the story.

The nobleman gives ten of his servant one mina (of gold) each. This was worth about £4,000. One made 1,000% profit, one 500%, and another hid it. The first two get to govern several cities, the third gets nothing. The reason is that, until Archelaus returned, it was completely uncertain whom Caesar would choose to be king, either Archelaus or his brother Antipater (a much better ruler). If Caesar had chosen Antipater, those who had traded with Archelaus’ money would have been marked men. The one who hid his mina in the ground would have been able to claim that he supported whichever of the claimants won. So the moral is a call to nail one’s colours to the mast, to be publicly loyal, even when things could go either way.

The story ends with the chilling, and probably historical postscript: “But as for these enemies of mine who did not want me to be king over them — bring them here and slaughter them in my presence.”

In my book I take this story as a way Jesus tried to dampen down the enthusiasm of his followers for an imminent arrival of the kingdom of God – that it would have very serious consequences. It fits well into the setting of the final walk up to Jerusalem.

THE COLT. How did Jesus enter Jerusalem?

When Jesus arrived at Bethany, just an hour’s journey to Jerusalem, he sent a couple of disciples (not necessarily from the Twelve), to a village on the other side of a small valley where Jesus had organised a secret sign with his Jerusalem supporters:

“Go into the village ahead of you, and as you enter it you will find tied there a colt that has never been ridden. Untie it and bring it here. If anyone asks you, “Why are you untying it?” just say this: ‘The Lord needs it.’”

(Luke 19.30-31, Mark 11.2-3. Mark adds Jesus’ promise that the colt will be returned).

It is deeply ingrained in Christian spirituality that Jesus entered Jerusalem on a donkey, thus showing his humility. But that is not what Mark and Luke say. They say he rode a ‘pōlon’ – a foal or colt – normally a young horse., hough it could mean more generally a young animal. Matthew and John both say he rode in on a donkey, explicitly because of the prophecy of Zechariah, the penultimate book of the Old Testament, which they both quote:

- Rejoice greatly, O daughter Zion!

- Shout aloud, O daughter Jerusalem!

- Lo, your king comes to you;

- triumphant and victorious is he,

- humble and riding on a donkey,

- on a colt, the foal of a donkey.

However, the initial meaning of ‘pōlos’ is a young horse. And both Mark and Luke add the detail that it was ‘a colt that has never been ridden’, i.e. a young horse that has not been broken in. You do not break in a donkey. What you largely do with a donkey is get it used to being tied up. (According to the Stockyard website, horse will respond to attempts at training by jigging or rearing. A donkey will freeze).

So I think Jesus rode in on a fine young horse, making his entry as public as possible. He had to ride something to do that, or he would simply have become lost in the crowd. Unlike other times when he entered Jerusalem incognito (as in John 7.10-15).

APPROACHING JERUSALEM

Only Luke tells us of the last stage of Jesus’ journey. It is clearly a piece of independent tradition which fits slightly awkwardly into the framework of the triumphal entry. My guess is that Luke wrote his account first, so that the story followed directly on from the chilling story of Archelaus’ rise to power. Luke fitted in Mark’s account of the triumphal entry after discovering Mark’s gospel, possibly in Rome about 62 AD. That does not mean it did not happen. It certainly makes psychological sense:

‘As he came near and saw the city, he wept over it, saying, “If you, even you, had only recognised on this day the things that make for peace! But now they are hidden from your eyes. Indeed, the days will come upon you, when your enemies will set up ramparts around you and surround you, and hem you in on every side. They will crush you to the ground, you and your children within you, and they will not leave within you one stone upon another; because you did not recognise the time of your visitation.”’ (Luke 19.41-44)

This clearly links with the prophecies of the end times which are recorded in Mark 13 and Luke 21. Traditionally they were remembered as part of Holy Week, and again they make psychological sense in that place. In my book I added in the marvellous poetry of Luke 13.34:

“Jerusalem, Jerusalem, the city that kills the prophets and stones those who are sent to it! How often have I desired to gather your children together as a hen gathers her brood under her wings, and you were not willing! See, your house is left to you. And I tell you, you will not see me until the time comes when you say, ‘Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord.’”

I could not resist combining the two passages, making one long song of lament. Did Jesus in fact sing it? The word for ‘wept’ does not mean tears; it means calling out. Or, as in my book, ‘keening’. The verses express well Jesus’ sense of tragedy which has haunted him for weeks if not for months.

WHERE WERE THE CROWDS?

It seems a weird question. But if Jesus entered the temple at the end of a long day walking up to Jerusalem, say at 4 o’clock in the afternoon on Palm Sunday, most of the pilgrims would already have been in the Temple. Jesus would then have met them when they were coming out, and that is how I have described it.

However, suppose we have got the day wrong? In the gospels no day is specified. It was Bishop Cyril of Jerusalem (315-386) who started the tradition of celebrating Holy Week commencing with Palm Sunday. But what if John is correct when puts the feast at Bethany as being six days before Passover, That would make it either Friday evening, i.e. the beginning of the Great Sabbath, the sabbath before Passover) or Saturday evening (after dusk). This would put the driving out the traders and the occupation of the Temple on Friday during the day, and Jesus’ arrival into Jerusalem on Palm Thursday. If Thursday was the day, then Jesus would have arrived with the mass of pilgrims ready to undergo the week-long rituals of purification before Passover. (Wall Street Journal 19/4/19) And he would have ridden in along with a great crowd of pilgrims anxious to get their first admittance into the sacred precincts.

Who is right? Me or the tradition of the Church? Ah, well …

BUY IT NOW!

Jesus the Troublemaker – his last eight days

£9.99 from bibleinbrief.org