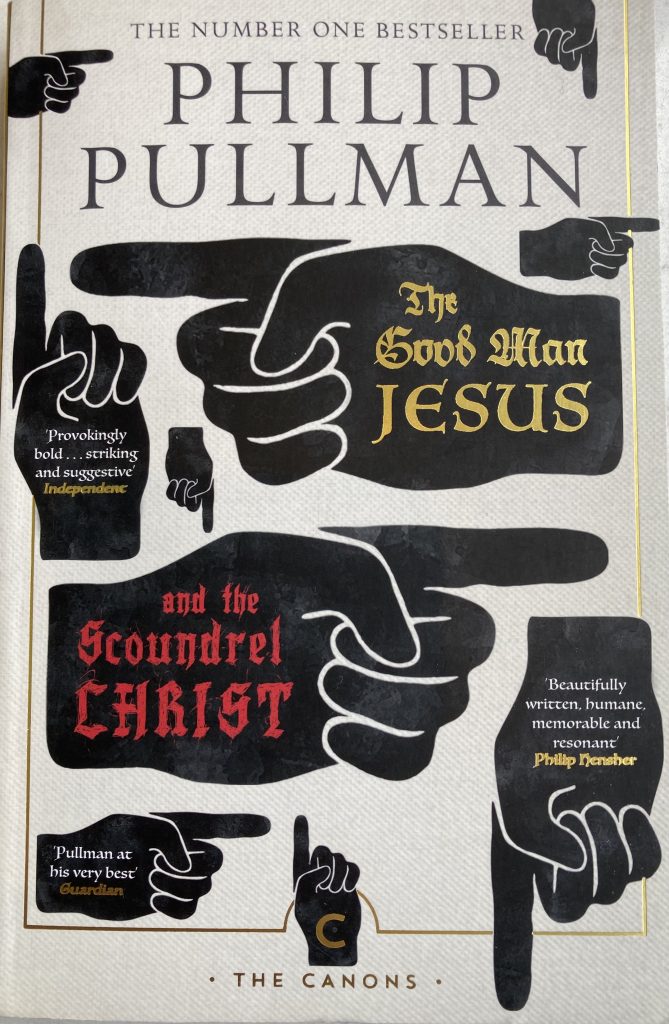

THE GOOD MAN JESUS AND THE SCOUNDREL CHRIST

In 2010 Philip Pullman published his novel about Jesus. The original back cover had the sublimely simple message “This is a story.”

The novel is a strange mixture of complete imagination and biblical accuracy. His account of the teaching of Jesus is one of the best accounts I have come across. But the plot introduces a second character, Jesus’ younger brother Christ, their mother’s favourite, who acts as a chronicler of Jesus’ ministry. He both hero worships his older brother and also criticises him because he thinks that Jesus is too careless about his reputation. So Christ adds miraculous details to what he actually witnessed or was told about. Christ hopes to ensure that Jesus makes a real impact on the world; he is the one who tempts Jesus in the wilderness to take the obvious routes to success – a quite brilliant section. When Peter calls Jesus the Messiah and Jesus tells him to shut up, it is Christ who invents the saying about Peter being the rock on which the church will be built. (Indeed, I agree with Pullman in classing this saying as a simple invention, but by the writer of Matthew).

Jesus is shown as a blunt prophetic figure whose fundamental faith is that “God loves us like a father, and his Kingdom is coming soon.” He has no wish to be known as a miracle-worker and has a very conflicted relationship with his family. Where Pullman diverges from the gospel accounts is at the garden of Gethsemane. Instead of praying “Not my will but yours be done”, Jesus realises that his whole life of faith has been an error – there is no God and no coming Kingdom. He goes to his trial and death as an atheist. The resurrection appearances are stage managed by his younger brother Christ who looks quite similar. The purpose of this action by Christ, guided by the mysterious figure of the Stranger is to create a world-wide Church which might do some good, as well as bad. As the Stranger tells Christ, ”History belongs to time, but truth belongs to what is beyond time. In writing of things as they should have been, you are letting truth into history. You are the word of God.”

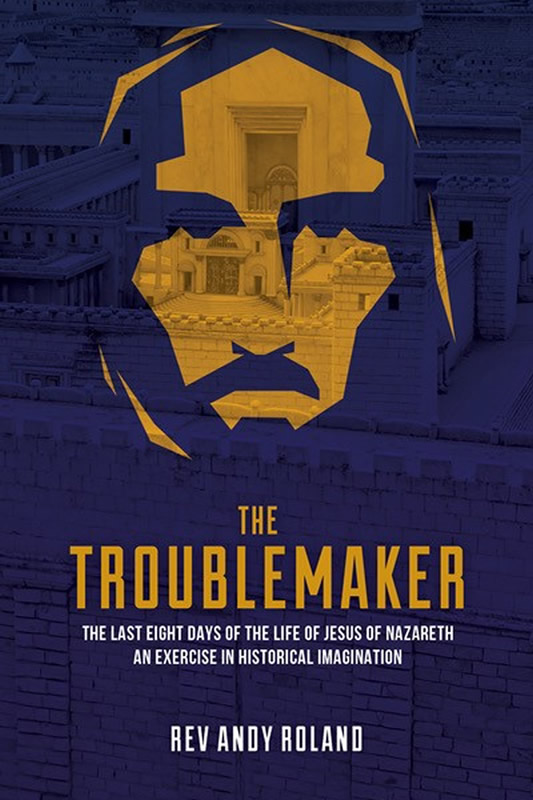

JESUS THE TROUBLEMAKER

I published my book ten years later in 2020. I describe the last eight days of the life of Jesus, starting a couple of days before his entry into the Temple at Jerusalem. This week is recounted in remarkable detail in the gospels. A distinctive feature of ‘Jesus the Troublemaker’ is that Jesus is placed firmly into his Jewish context. All the names are Aramaic – Jesus is Yeshua, Simon Peter is Shim’on Kefa. The Temple worship is significant. The Last Supper is a Passover meal complete with Jewish prayers. At the same time all of Jesus’ words are contemporary. Jesus words after the Last Supper, “Satan has demanded to sift all of you like wheat”, becomes “The Enemy has insisted on putting all of you through the shredder.”

I believe that the key to Holy Week is just eleven words in Mark. After describing how Yeshua drove the traders out of the Temple courts, Mark alone adds ‘he would not allow anyone to carry trade goods through the temple.’ (Mark 11.16). That was possible only if there were enough burly Galilean pilgrims at each gateway to outnumber the Temple guards. In other words, it was not a demonstration, it was an occupation. This continued the rest of the week, because the following day the leading priests asked “‘By what authority are youdoing these things? “ No wonder the authorities wanted to get rid of him.

My book follows closely the gospel of Mark, supplemented by passages from Luke and John. The key gain about writing it as a novel is that you pay close attention to location and timing. For instance, Pilate’s headquarters were most likely in the Roman barracks in the northern wing of Herod the Great’s palace, just ten minutes from Caiaphas’ palace. This also makes sense of Luke’s account of the investigation by Herod Antipas, whose palace was in the southern wing, just five minute’s walk away. One piece of pure guesswork is that Yeshua’s men followers stayed in a different house from his woman followers, i.e. the houses of Shim’on the Leper (Mark 14.3) , and Eleazar, Marta and Miryam (John 12.2), simply because there were too many guests for just one household.

Throughout ‘Jesus the Troublemaker’ the narrative stays close to Yeshua, his words, actions, thoughts and feelings. That is impossible when telling the story of the resurrection. That is recounted in a letter by one of Yeshua’s close woman followers Salome/Shlomit to her husband. There are problems with the gospel accounts of the resurrection. Mark ends his gospel before there are any appearances of the risen Jesus. John’s account of the appearance to Miryam of Magdala does not fit easily into the other accounts. I believe I have squared the circle by means of one simple question: ‘Where was Peter?’

WHO IS PHILIP PULLMAN?

Philip Pullman was born in 1946. He got a third in English at Oxford and went into teaching. His first book was in 1972. The first part of his brilliant ‘’Dark Materials’ was published in 1995, that of his ‘Book of Dust’ trilogy 2017. ‘The Good Man Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ’ came out in 2010.

The last has a fascinating afterword in which he describes his non-faith journey, starting with his strong belief in the Christian faith as a child. This he found impossible hold onto as a teenager. Like his Jesus in Gethsemane, he found that “the silence on His (God’s) part was complete.” But he alsosaid that he “can’t escape his Christian background”. His preparation for writing ‘The Good Man Jesus…’ was reading the four gospels in three different translations. He also read various apocryphal gospels, but “they’re just not very good.” He is aware of the contradictions within the gospels, and how they were explained down the centuries. But rather than smooth and polished interpretations, he “preferred the roughness and mystery of the originals.”

To summarise, “Jesus was a man … and no more than man, but Christ was a fiction.”

WHO IS ANDY ROLAND?

I was born in 1945, so I and Philip are close contemporaries. We both learned about the Christian faith at school. I held onto faith throughout my teens, making a serious commitment at university. At Oxford I got a second in history. The subject makes one ask constantly, ‘What actually happened?’ I became convinced then, and remain convinced now, that Mark is the equivalent to a first-hand account, plausibly written by the young man who was almost arrested in Gethsemane wearing nothing but a linen cloth but who ‘left the linen cloth and ran off naked.’ (Mark 14.52). At Oxford Andy relied on three arguments which allowed him to hold to faith:

1 As a historian I thought of Mark as essentially a first-person account. So presumably Jesus did rise from the dead. So presumably God is.

2 I found that I work better as a human being when I start the day with prayer. I could not conceive that the universe to be so chaotic that one part works better on the basis of that which is not the case.

3 I am completely convinced that I was not the most spiritually advanced person on earth!

After two years of teaching, I became a personnel administrator for nine years and then felt called to ordination in the Church of England. After 30 years as a priest in South London I retired and immediately began writing books, starting with ‘Bible in Brief’ and currently ending with ‘Journey through Lent with Jesus’.

WHO TO BELIEVE?

Philip Pullman has written a book which utilises as much of the gospel accounts as an atheist finds credible. The Good Man Jesus is indeed a good and challenging figure but fundamentally unimportant. It is the Jesus seen through the eyes of a powerful faith community, i.e. the Church, which is significant for good and ill, and it is the Scoundrel Christ who creates this story.

I find that Mark gives us real insight into the person and character of Yeshua, often in quite minor details which don’t make it into the other gospels. For instance, when Yeshua calms a storm at sea, he does not ask the disciples the strange question “Why were you afraid?” (Mark 4.40, all English translations), but the much stranger question (in the Greek) “How were you afraid?”

Luke uses Mark responsibly, so his account is worth taking seriously, and clearly has his own sources for the final 24 hours of Yeshua’s life.

I have been persuaded recently by Richard Baukham’s work that John was written not by the Galilean son of Zebedee but by a Jerusalem disciple also called John/Yechoanan. That makes his witness to actual events significant.

Matthew sad-to-say editorialises and skews Mark’s account to make Jesus a more spiritual and heavenly figure, thereby diminishing the impact of the real Yeshua Ish-Natzeret. In my opinion Matthew should be placed in a separate section of the Bible entitled ‘New Testament Apocrypha’ along with 2 Peter and perhaps the Book of Revelation.

In ‘Jesus the Troublemaker’ Andy does make assumptions and decisions, but all are described in the notes at the end of each section, so, as in maths, you can check his workings-out.

Is it a good thing to write/read a novel about the life of Jesus? It’s worth a debate!