Introduction

There is a story of a waiter in a ’nouvelle cuisine’ restaurant asking a diner, “How did you find your steak, sir?” The response was, “I lifted up a pea and there it was.” Surely an article which appears to ask a similarly simplistic question, merits an equally short reply.

However, there may be something to help us read John if we think about the technology which he could have used.

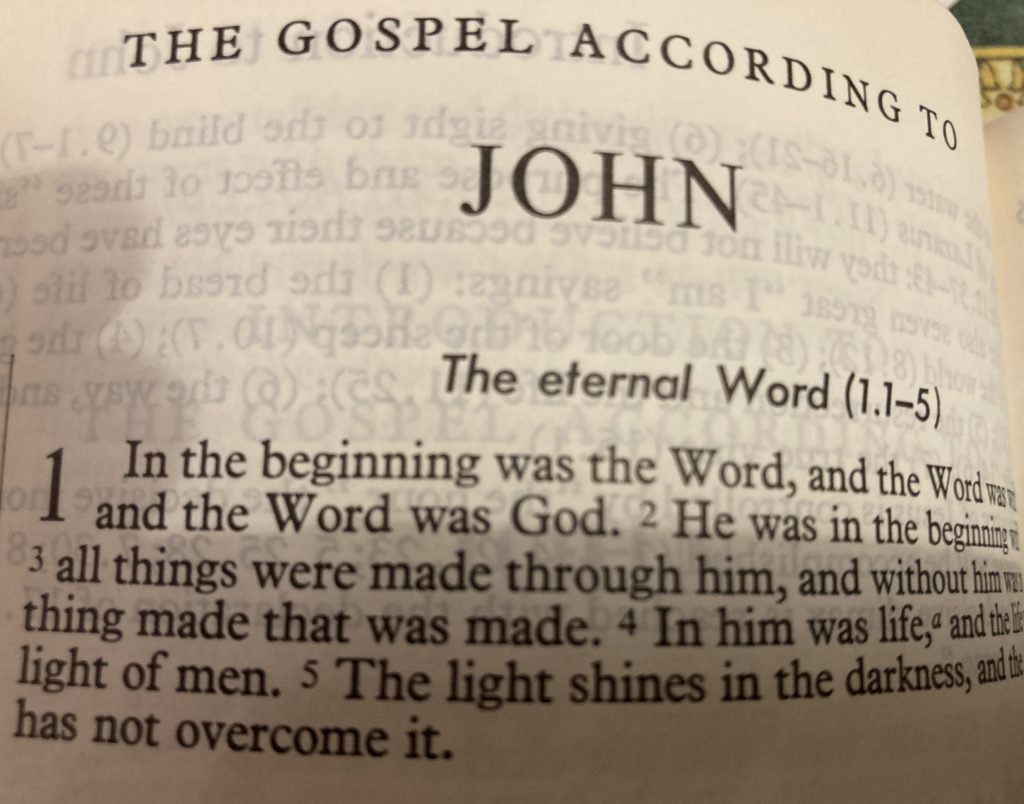

Chapters and verses

When we open a Bible at the beginning of John’s gospel, we immediately see a large number ‘1’. In other words, we are being informed that we are at the start of chapter 1. But for the first 1200 years of the Christian church there would have been no numbers at all, no chapter divisions and no numbered verses. These are incredibly useful in finding our way around the text, so we should be very grateful to our own Archbishop of Canterbury, Stephen Langton, who divided the Bible into chapters around 1180 and to Robert Etienne from Geneva who added verses in 1551.

They are useful but they can skew the way we might read the Bible. Is there a better way of subdividing the text?

Books and parchments

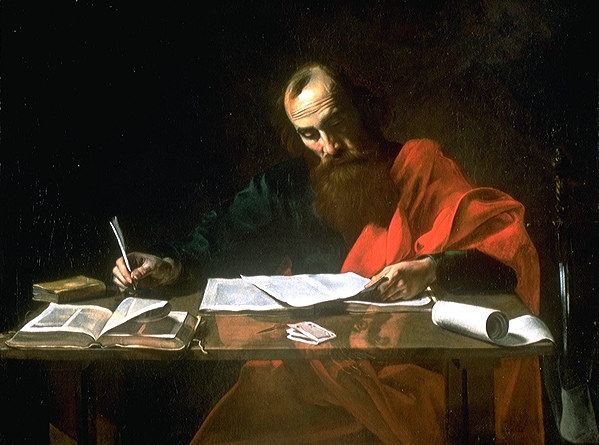

In 2 Timothy 4.13, Paul asks Timothy, “When you come, bring… the books and above all the parchments…” What were they?

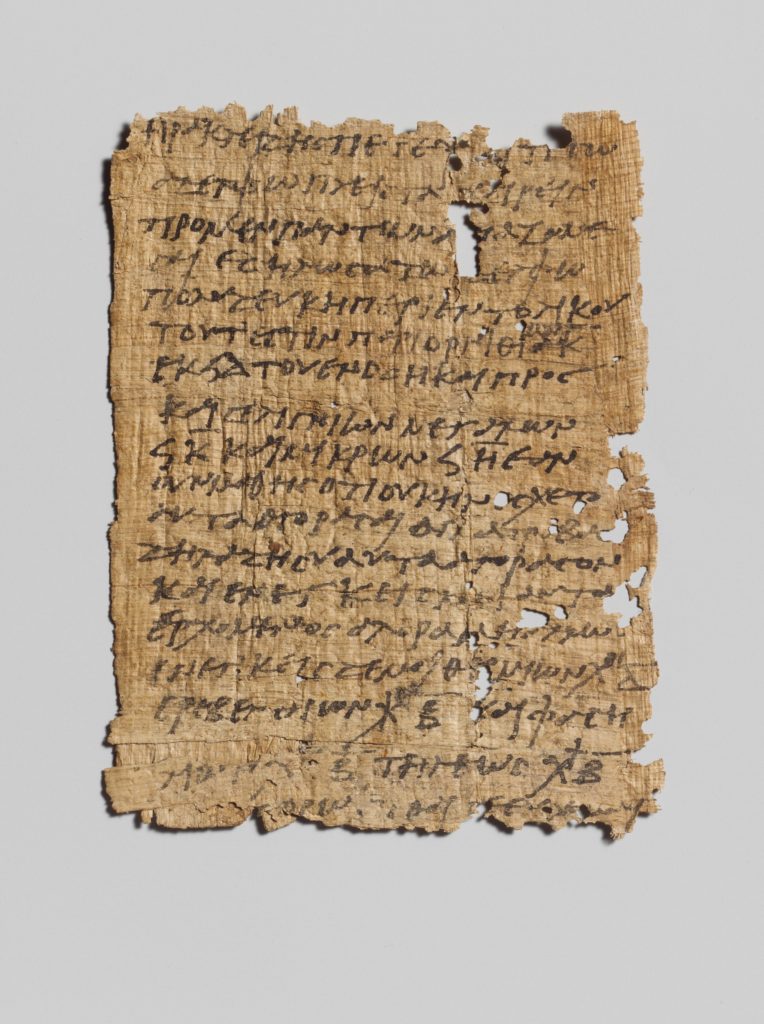

But Paul clearly values his parchments more. These were a more informal writing material. They originated in a wooden tablet with a surface of wet clay as an instant form of writing, see photo. In the first century tablets of animal hide or papyrus took over. If you cut the hide or papyrus into page-sized sheets and bound them together, you have the ‘codex’, the ancestor of the modern book. Advantages compared with scrolls is that they were easier to carry, could be read without using both hands, you could write on both sides, and it was easy to flip pages over to check references. Lawyers used them as a help in court; you could jot down anything that interested you, and keep track of your accounts. If it was parchment, i.e. animal skin, pages could be washed, cleaned and re-used, useful in a notebook for jotting random things down. By the end of the first century, parchment notebooks had arisen as an alternative to wax tablets and filled many of the same roles for writers and students. Papyrus was used when cheaper, especially in Egypt.

Books were papyrus scrolls of published works. They were what you would get if you went to a bookseller in Rome. In 79 AD one wealthy house in Herculaneum had 1,800 papyrus scrolls. They remained the main form of publishing literature for the next 200 years. They could be up to 11 metres long, so could, for example, contain the Gospel of Matthew.

And a codex was about 25% cheaper to produce than a scroll.

By 100 AD the Roman poet Martial was extolling the virtue of this new book technology, and even published several books of epigrams using codices, not scrolls

A Christian thing

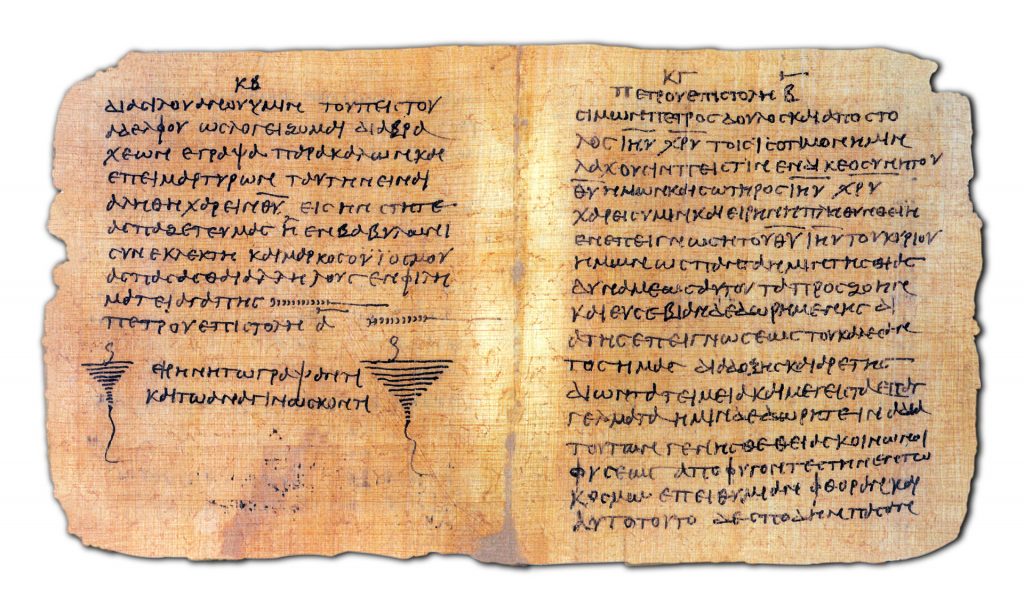

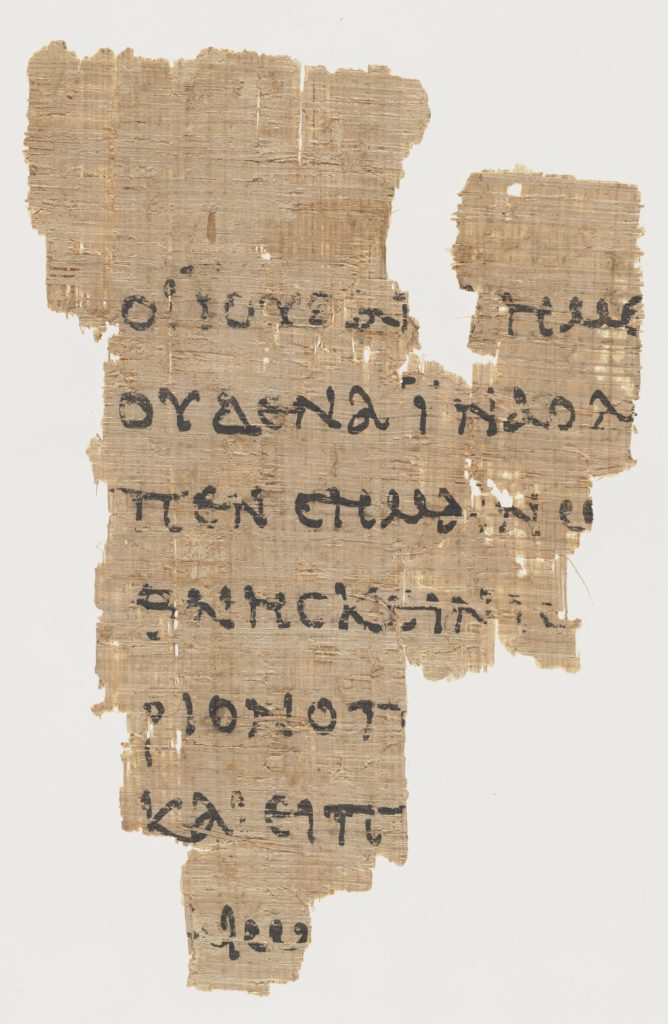

The earliest piece of the New Testament, the Rylands fragment of part of John 19, 125 – 160 AD, is from a papyrus codex, written on both sides. It is probable that all Christian writings were in this form. Shorter books might have occupied just four sides. Is there any evidence?

Yes. A Bible index shows fifteen short pieces of writing among the New Testament letters, ranging from 606 lines just 40. Excluding the two longest (Ephesians and Galatians, 606and 532 lines) and the three shortest (Titus, Jude and Philemon, 93, 63 and 40 lines) we are left with ten short writings of strikingly consistent length. These ranging from 1 John and 1 Peter (282 and 233 lines) to 2 Thessalonians and 2 Peter (105 and 147 lines). The average number of lines for the ten short books is 195 lines. My guess is that a simple four- or eight-page codex would have been an ideal format.

From blog to book.

The Gospel of John reads quite differently from the other gospels. The latter are basically an accumulation of short stories of a paragraph or two in length or a short collection of sayings. John has lengthy passages which follow a line of argument, often starting with a miracle (or ‘sign’) followed by a theological response. It makes absolute sense to read them as independent units. Perhaps that is how John wrote them (or dictated them) originally; each mini-book (tabellus or libellus in Latin) would be complete in itself. When they were collected into one large codex incorporating the earlier small ones, I would expect to see roughness in transitions.

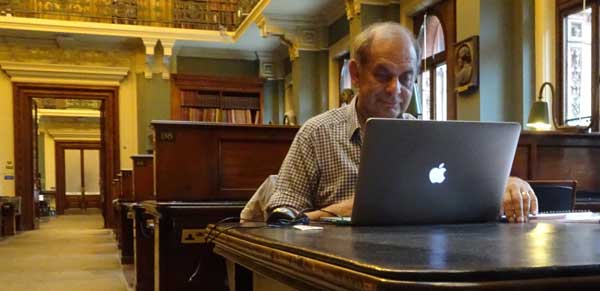

A Greek letter

I like this idea because it is how I work. Later this year I aim to publish a long book, ‘The Church has a Past – has it got a Future?’ I have multiple blogs that I have sent out in the past with a view to gathering them together in a full-length book They are all of a certain length, round about 1,500 words, because the medium and it s audience demand a certain restraint; either that or a division of one blog into two. Right now I am in the process of revising them in the hope of publishing the whole book later this year. I hope to find a traditional publisher, because it will need a lot of editing. Perhaps John wrote under similar constraints of technology and audience.

John’s New Look

What would John look like if we put hot into sections of around 200 lines each? And what would they mean?

Chapters 1 – 3. (186) lines. There are various sub-sections, but if you take it as a whole it has a clear structure, all introducing the reader to Jesus

1.1-18. Introduction; the eternal Message and the messenger

1.19-34. John’s witness to Jesus

1.35-51 First disciples

2. 1-12 First sign of glory

2.13-25 Reactions to Jesus (riddle of death and resurrection)

3.1.12 Potential disciple (Nicodemus)

3.13-21 Reflection on 3.1-12

3.22-30 John the Baptist John by Giotto

3. 31-36 Reflection.

It seems to me that it is particularly directed to the followers of John the Baptist, who still existed when Paul was missionizing in Greece (Acts 18.25). Perhaps the story of the wine at the wedding in Cana was an indirect comment on John the Baptist taking no wine or strong drink (Luke 1.15).

Chapter 4.1-45. (83 lines). A one sheet document for the Samaritan mission

Chapter 5. (92 lines). Healing at the pool – appeal to Jews, esp. re sabbath

Chapter 6 (100 lines). Feeding the 5,000 and teaching on eucharist

.

Chapters 7-8 (omitting 7.37-39 and 7.53-8.11, added in later). (120 lines) Feast of Tabernacles, disagreements over Jesus

Chapters 9-10 (165 lines). Healing of blind man, dispute with Pharisees.

(10.22-42 Feast of Dedication)

Chapters 11-12 (223 lines). Bethany, entry to Jerusalem, final summary.

Chapters 13-14 (140 lines). Last Supper and Jesus’ promises

Jesus’ teachings in response to questions by 3 named disciples.

Chapters 15 – 16 (122 lines) More teaching after Last Supper.

Chapter 17 (54 lines) Jesus’ prayer after the Last Supper

Chapter 18.1-27 (60 lines) Jesus’ arrest and first trial

Chapter 18.28 – 19.42 (134 lines). Trial by Pilate, crucifixion and death.

Chapter 20 (70 lines) Jesus’ resurrection, gift of the Spirit

Chapter 21 (60 lines) Second call of the disciples

Seeing the big picture

When I was a teenager, my best friend Mick Reid and I once read through the entire letter to the Galatians in one sitting. It was a very dramatic experience , and we caught a sense of Paul as he actually was – passionate and sometimes over-passionate. If we want to get a sense of the writer and his work, we need to experience it as a whole.

The division of John’s gospel above is not meant to be an academic exercise, but a call to read the gospel in a new way. By setting aside ten or fifteen minutes to read aloud (which is what reading meant until the 5th century AD), we will have an immediate encounter with John and his Lord. Maybe something to do on a Sunday afternoon.

I have tried it, using J B Philips translation. It works! John’s particular message to each group he is addressing becomes clear, particularly in the last few paragraphs of each section.