Between the Testaments

What happened between the end of the Old Testament and the birth of Jesus? Answer, a lot! There are detailed accounts in the Apocrypha of the revolt of the Maccabees in 167 BCE. In fact if it hadn’t been for them, Galilee would not have been conquered and converted to Judaism!

In September 2014 the Israeli newspaper Haaretz published a short account of this crucial bit of history. Here it is:

Revolt of the Maccabees: The True Story Behind Hanukkah

The ancient Israelites, led by Judas Maccabeus, did vanquish the oppressor Antiochus – but Greek rule would only be shaken off 20 years later under Judas’ younger brother.

Hanukkah, the Jewish festival of lights, celebrates the Maccabean Revolt (167-160 BCE), and the narrative that Jewish rebel Judas Maccabeus vanquished the evil Greek emperor Antiochus and rededicated the Temple, at which the miracle of the oil occurred.

All true, with the possible exception of the miracle of a day’s supply of lamp oil lasting eight days: but that narrative skips over the schisms within the ancient Hebrews’ society, mainly – who exactly was rebelling against who.

In the late 6th century BCE, the Persian emperor Cyrus the Great let the Jews go home after decades of exile in Babylon, and turned Judea into a semi-autonomous theocracy run by the High Priest and the powerful priestly families in Jerusalem.

Gold coin of Cyrus as king of Lydia

GJudea’s semi-autonomy would continue for centuries – after Alexander the Great conquered the region in the 4th century BCE; and it would persist under the Ptolemaic Kingdom, based in Egypt, and the Seleucid Empire in the north, which dominated Israel at different times.

During this time, the Hellenic domination of the Near East spurred economic development; and the dominant urban class in Judea, the priests, became increasingly wealthy and Hellenised.

But the majority of Judeans were rural farmers. They were not becoming rich, nor were they adopting the ways of the sophisticated, cosmopolitan Jerusalemites. This socio-economic divide would play a decisive role in the following events.

The rise of Antiochus IV

In 175 BCE, Antiochus IV Epiphanes ascended to the throne of the Seleucid Empire, which at that point controlled Judea.

Coin of Antiochus IV Epiphanes

‘of the victorious god manifest Antiochus’

“of the victorious god manifest king Antiochus.”

Wanting to outdo his father and capture Egypt, and unite the Seleucid and Ptolemaic kingdoms into one superpower, Antiochus needed money. When a faction of Judaean priests offered to pay him to replace the High Priest Onias III with his younger brother Jason, he took the money. Why not?

But this created a dangerous precedent. Three years later, another rich priest, Menelaus, offered even more money and was appointed high priest by Antiochus. Jason went into exile.

Menelaus however was not from the line of high priests and his appointment upset the conservative Judaeans. Worse, he took treasures from the Temple to pay Antiochus, which was sacrilege – and on top of all that, he was a radical Helleniser. His appointment was not popular, and had to be enforced by force.

Meanwhile in Antioch, Antiochus decided it was time to make history. He led his army to Egypt to achieve what his father had not. Upon rumours of his death in battle there, civil war erupted among the Jews in Jerusalem as Jason reappeared from exile, and led a popular revolt against Menelaus.

Reign of terror

But Antiochus was not dead. He had been humiliated by the Romans and forced out of Egypt. Yet while retreating, he heard of the struggle in Jerusalem – and reinstated Menelaus.

Once back in power, Menelaus led a reign of terror and set out to Hellenize the Jews. A statue of Zeus was placed in the Holy of Holies, among other violations of Jewish law.

Many pious Jews resisted Menelaus’ measures, some by martyrdom, others by escaping into the wilderness, and still others by active revolt.

Most prominent of these rebels was the group led by Mattathias of Modiin and his five sons – of whom Judas Maccabeus proved to be the most able and drew the rest of the Jewish rebels into his camp.

Judas and his band of rebels staged guerrilla warfare against Hellenised Jews; Menelaus in response summoned the Greek armies from neighbouring Seleucid provinces.

Judas crushes the Greeks

The first army to arrive, from Samaria in the north, was led by Apollonius. Judas was tipped off, and crushed the small army on the road to Jerusalem. He was to take Apollonius’ sword and use it until his death.

Next came a larger force, led by Seron, from Palestine in the west. Once again Judas ambushed them, and 800 enemy soldiers were killed.

Alarmed, the Seleucids dispatched a real army, from Antioch, led by two generals, Nicanor and Gorgias. But once again, Judas proved his military prowess: he routed the army and seized its weapons.

Even after this defeat, the Seleucid army remained bigger and badder than the small rebel force. There was real danger that it would press on and crush the rebellion.

But at this point, the rebels caught a lucky break. In 167 BCE, King Mithridates I of Parthia attacked the Seleucid Empire and captured the city of Herat, in modern-day Afghanistan. Antiochus had to concentrate his forces on the Parthians.

With the Seleucid army thus preoccupied, the rebels captured Jerusalem in 164 BCE, though the Akra Fortress overlooking the Temple Mount remained loyal to Antioch (within it, Assyrian soldiers and Hellenised Jews would remain steadfast).

The Temple was rededicated and the eight-day holiday of Hanukkah was created, modelled on the eight-day holiday of Sukkot. The story of the miraculous oil lasting eight days is apocryphal: It would only appear centuries later in the Talmud (Shabbat 21b).

Jerusalem under siege

With his power base in Jerusalem firmly established, Judas began attacking gentile cities around Judea, though the purpose seems to have been not subjugation, but spoils. Then he returned to Jerusalem and laid siege to the Akra.

By this time, following Antiochus’ death in Parthia in 164 BC, the Seleucid Empire was ruled by Lysias, regent for the child King Antiochus V Eupator. Lysias set out to destroy Jerusalem and crush the Maccabean revolt once and for all.

After beating Judas in battle south of Bethlehem, Lysias laid siege to Jerusalem.

The rebel Jews’ situation was desperate. They lacked the supplies to withstand a lengthy siege, not least because that year was a shmita year.

Once again, luck intervened. Philip, one of Antiochus’ generals, revolted and set out to storm the capital, Antioch. Anxious to return to the capital, Lysias reached terms with the Jerusalemites. Judea was restored to its former semi-autonomous state and Menelaus was replaced as High Priest by Alcimus, a moderate.

But as soon as Lysias left, fighting broke out again between Judas’ rebels and the moderates who supported Alcimus. An army led by the Seleucid general Nicanor was dispatched to aid the moderates. In 161 BCE, Judas beat Nicanor’s army in the Battle of Adasa and Nicanor was killed.

That same year, after defeating Philip, Lysias and Antiochus were killed by Antiochus’ cousin Demetrius I Soter, who ascended to the Seleucid throne. He dispatched another army, led by the general Bacchides.

They faced off in the Battle of Elasa in 160 BCE. Judas’ band was no match for that 20,000-strong army. The Jews were crushed and Judas was killed.

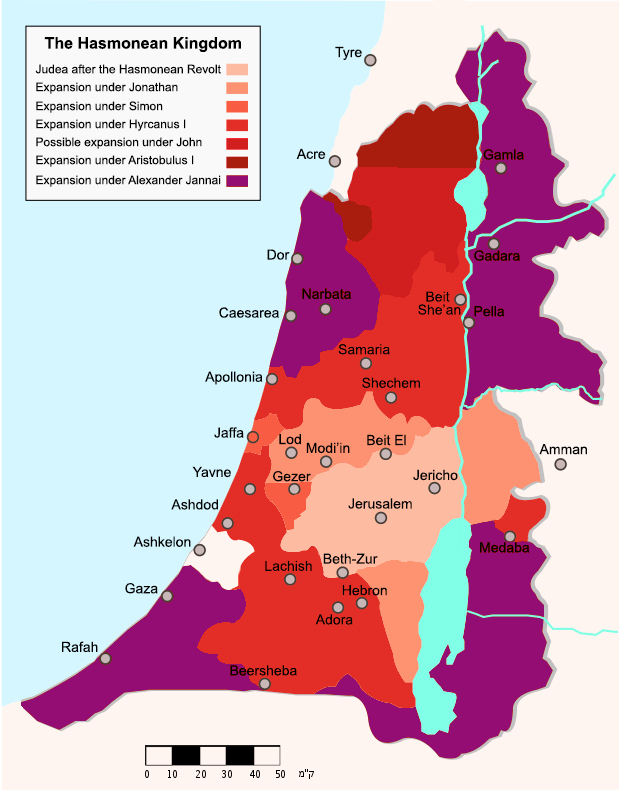

Thus the revolt ended in tragedy. But some years later, changes in the geopolitical landscape would lead to Judas’ youngest brother Jonathan Apphus ascending to the high priesthood, and to the establishment of the Hasmonean Dynasty that would rule an independent Judaea from 140 to 37 BCE.

Late Hasmonean coin

To continue…

To continue the story of the Maccabees beyond the Haaretz article, the most significant event for Christians was the conquest of Galilee.

Galilee Galilee, or Galil, simply means region. Its full name was Galil Goyim or Region of the Gentiles. But in 104 BCE the Hasmonean high priest and king Aristobolos I conquered and annexed Galilee, leading to an influx of Jews from Judaea. So it seems that Jesus was born Jewish courtesy of the Hasmoneans.

Herod I

The Hasmonean dynasty fell when Herod defeated them in war. He then ruled as a client king under the Romans, and appointed no less that six high priests. He built a large number of palaces, a big one in Jerusalem, four in Jericho and the amazing one at `Masada. He also rebuilt the Temple in Jerusalem on a massive scale. At the end of his life he executed three of his sons and his beloved wife Mariamne. The ‘massacre of the innocents’ in Matthew 2 was not out of character.

After Herod I

In his last will Herod I made his son Archelaus ruler of Judaea; but he was such a bad ruler, famed for his cruelty, that after nine years the Romans took over and exiled him to Gaul. From 6CE Judaea and Samaria were ruled by Roman prefects in conjunction with the high priest whom they appointed. Herod Antipas, another son of Herod I, was made ruler of Galilee and stayed in power right through to 39 CE. Jesus called him ‘that fox’.

The start of the New Testament.

‘In the fifteenth year of the reign of Emperor Tiberius, when Pontius Pilate was governor of Judea, and Herod was ruler of Galilee, and his brother Philip ruler of the region of Ituraea and Trachonitis, and Lysanias ruler of Abilene, during the high-priesthood of Annas and Caiaphas, the word of God came to John son of Zechariah in the wilderness.’ (Luke 3.1-2)

Now read on…

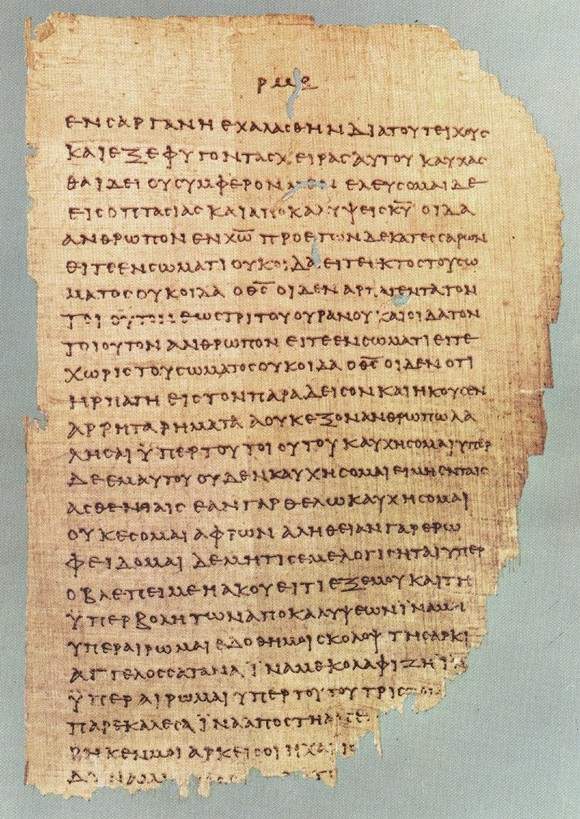

Part of Paul’s letters