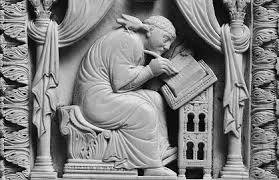

GREGORY THE GREAT

c.540 – 605

The end of the world

Gregory was born to a rich and ancient senatorial Roman family about 540, during the war in which the Empire of the East reconquered Italy from the Goths. The war lasted for twenty years, from 535 to 554. Rome was captured five times by the two sides alternately, in 535, 546, 547, 549 and 552. In 541 a devastating plague killed up to a third of the population. In 549 the Goths captured Rome again, determined to kill all the men. Presumably Gregory’s family fled to their estates in Sicily. Then in 568, after 14 years of peace, the Lombards, another German tribe, began their conquest on Italy. In 589 there was a great flood, followed the next year by another terrible plague. As Gregory said, “She that once appeared the mistress of the world, we have seen what has become fo her, shattered … by immense and manifold misfortunes… Ruins on ruins… Where is the senate? Where are the people? … And we, the few who remain, every day we are menaced by scourges and innumerable trials…”.

An ordered life of prayer

Gregory started life in the classical mould. His father was a Roman senator. Gregory was trained in grammar, rhetoric, the sciences, literature, and law. At the age of 33 he was made City Prefect, the highest civilian office. Two years later, on the death of his father, he renounced his wealth and career, turned his family home into a monastery and founded six more monasteries on his family estates in Sicily.

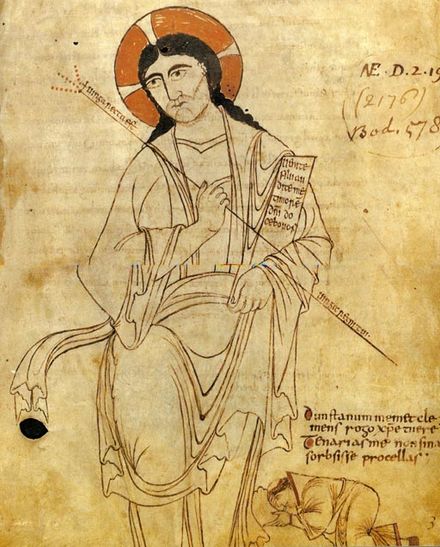

“When I lived in a monastic community, I could… devote my mind continually to the discipline of prayer….” He particularly cherished contemplation, “in that silence of the heart, while we keep watch within through contemplation, we are as if asleep to all things that are without.” When Gregory was Pope, he talked to his deacon Peter of “the unclouded beauty of my former peace.”

He continued to live a monastic lifestyle to the end of his life, taking some brother monks with him when he went to Constantinople as papal ambassador. He may have used the Rule of St Benedict which had been written about the time he was born. It was certainly through the combined fame of Benedict and Gregory that Benedictine monasticism became the pattern of monasticism throughout Western Europe for the next 1500 years.

The Empire in Italy disintegrates

When Gregory was 39, Pope Pelagius called him out of his monastery to be his ambassador at the imperial court at Constantinople. The Pope wrote, “The territory aroundRome is without any garrison. The Exarch write that he can do nothing himself, being unable to defend the region of Ravenna itself.” Gregory stayed for seven years, but could not persuade the emperor Maurice to send troops, despite his popularity there, specially with the ladies. This was because of the twenty year war between Byzantium and Persia. Gregory did all he could to maintain the Roman commonwealth, not accepting the post of bishop of Romeuntil it was confirmed by the emperor 1,400 miles away. But effective links were becoming increasingly impracticable.

Ruling Rome

Against his will, Gregory was made Pope by popular acclamation. At once he had to defend Rome in not one but two sieges, being forced to negotiate with “the unspeakable Alruic”, duke of Spoleto in central Italy. He organised the city’s defences and water supply. He paid a regular ransom to the Lombard king in the north (an Arian Christian) and advanced the wages of the imperial troops. Indeed so great was the danger from the Lombards and so absent was any help coming from the emperor that in 692 he concluded a separate peace treaty with the Lombards, to the fury of the emperor. It took seven years of hard diplomacy to bring about peace between the Lombards and tByzantium, with the help of the Lombard king’s Catholic wife: “In fatherly affection, we exhort you so to deal with your most excellent consort that he may not to reject the alliance of the Christian republic. For, as we believe you also know, if he could bring himself to embrace its friendship, it would be profitable in many ways.”

Since civil rule and completely broken down, it fell to Gregory to support the poor of the city. The church had become wealthy. In many cities, landowner’s who found it impossible to pay their taxes to the emperor, surrendered their lands to the local bishop. The church owned many estates in Sicily, which had not been affected by the wars. Gregory supervised the administration of the church’s estates with care and efficiency, drawing up a register of all persons having regular receipts from the treasury. His concern was “not so much to promote the worldly interests of the church as to relieve the poor in their distress and especially to protect them from oppression.” He instructed his clergy to seek out all beggars and ensure they were fed before he himself sat down to eat. When a beggar died on the streets of Rome, he held himself personally responsible and publicly suspended himself from celebrating communion – effectively excommunicating himself. As he said in one of his letters, “I hold the office of steward to the property of the poor”.

Pastoral care

Gregory’s pastoral writing was enormous. While at Constantinople, he undertook a five year project, writing a commentary on the book of Job in 35 sections. He also wrote forty homilies on the gospels, four books of dialogues, giving numerous examples of miracles and healings, a commentary on Ezekiel, a short ‘Synodical Book” on how to administer the church. And over 850 letters.

The most famous book was the ‘Regula Pastoralis’, or ‘the Pastoral Office’, giving guidance to bishops. It was translated into Anglo-Saxon by king Alfred to help revive the Church in England after the Viking wars, and was used throughout Europe in the Middle Ages. Here is an extract: “The teacher must consider beforehand with careful meditation not only how he is to avoid preaching bad doctrine, but also how he is not to preach what is right too lengthily, too immoderately or too severely.” Useful advice today!

His theology was traditional. When he was at Constantinople, he argued fiercely against the views of Eutychius, the patriarch, who surmised that at the general resurrection, bodies would be ‘impalpable’, i.e. not physical. And he argued in favour of purgatory: “Each one will be presented to the Judge exactly as he was when he departed this life. Yet, there must be a cleansing fire before judgment, because of some minor faults that may remain to be purged away.”

Gregory’s pastoral heart is summed up by the title he chose for himself, still a principal title of Roman popes: ‘servus servorum Christi – the servant of the servants of Christ’

John Calvin, the 16th century reformer, called Gregory “the last good pope”.

The English

While Gregory was a young man, he saw some boys in the slave market in Rome with “fair complexions, fine-cut features and beautiful hair”. On asking where they came from, he was told they were Angles (as in Anglo-Saxon). He replied, “That’s appropriate, because they have angelic faces. It’s right they should become joint-heirs with the angels in heaven.” He asked the Pope to send him to Britain as a missionary, but his request was denied. Four years after becoming Pope , he sent some of the brothers from his monastery to preach the gospel to the English. But on reaching Milan, they got cold feet and asked Gregory to reconsider, as they “were appalled at the idea of going to a barbarous, fierce and pagan nation.” Gregory sent them on their way, with Augustine as their abbot, saying how much he longed to be with them. They arrived at the court of the king of Kent , who had a Frankish Christian wife. Gregory set up the administration of the new English church, with archbishoprics at London and York, emulating the provincial administration of Roman Britain. (The southern one moved to Canterbury after London had reverted to paganism). Gregory kept in close touch with the English mission through letters. One of the questions Augustine asked was, “May an expectant mother be baptised? And how soon after childbirth may she enter church?… And may a woman properly enter church after menstruation?… These uncouth English people require guidance on all these matters.”

Gregory replied with exquisite diplomacy, “I have no doubt, my brother, that questions such as these have arisen, and I think I have already answered you; but doubtless you desire my support for your statements and rulings…”. His answers were: why not?; any time; and, of course.”

The Jews

But he did adopt polices that harmed Jews economically. A synagogue was moved because its services could be heard by Christians; and slaves of Jews could claim freedom if they converted to Christianity — their masters could not sell them, and escaped slaves could not be returned to Jewish owners..

The net result was that throughout the middle ages, the papacy was a major, if unwilling, defender of Jews.

Ill health and depression

Gregory’s many-sided achievements would have been impressive in a man of good health. But this was far from the case. From his youth, “he was often in agony from gastric pain, perpetually worn out by internal exhaustion, and frequently troubled by a slow but chronic fever.” (Bede). And depressed. Here is part of one of his homilies:

“Since assuming the burden of pastoral care, I find it difficult to keep steadily recollected because my mind is distracted by numerous responsibilities …. One moment I am required to participate in civil life, and the next moment to worry over the incursions of the barbarians…

My mind is in chaos, fragmented but the many and serious matters I am required to give attention to…. I am often compelled by virtue of my office to socialise with people of the world, … so I find myself being sucked into their idle talk.

“Who am I! What kind of watchman (Latin Gregorius) am I? I do not stand on the pinnacle of achievement; I languish in the pit of my frailty. And yet although I am unworthy, the creator and redeemer of us all has given me the grace to see life whole and an ability to speak effectively of it. If is for the love of God that I do not spare myself preaching him.”

Lamed by arthritis at the end of his life, he died on 12th March 605 at the age of about 65.

Something to do

Please pray for church leaders everywhere, suffering the same strains as St Gregory did, whether Pope Francis, Archbishop Justin or Bartholomew the Ecumenical Patriarch.

Bibliography

Bede – The Ecclesiastical History of the English People

R H C. Davis A History of Medieval Europe

Ed. D Ayerst & A Fisher – Records of Christianity, volume 2 – Christendom