THE HISTORY OF HELL

The Four Last Things

I knew a priest went to buy some tobacco from a small tobacconist near St Paul’s on Christmas Eve. All the other shops were blazing with lights but not this one. The priest asked if he was not putting up any Christmas decorations that year. “Not during Advent, sir,” came the solid reply.

For over 1500 years the four weeks before Advent were marked by the church as a time of penitence and were used to reflect on the Four Last Things: Death, Judgment, Heaven and Hell. This blog is coming out on the fourth Sunday of Advent. So it is appropriate, if slightly antiquarian, for it to be about the History of Hell.

A good start for our refection is at a British army chapel service in the First World War…

- Our Padre were a solemn bloke,

- We called ‘im dismal Jim.

- It fairly gave ye t’ blooming creeps,

- To sit and ‘ark at ‘im,

- When ‘e were on wi’ Judgment Day,

- Abaht that great white throne,

- And ‘ow each chap would ‘ave to stand,

- And answer on ‘is own.

- And if ‘e tried to charnce ‘is arm,

- And ‘ide a single sin,

- There’d be the angel Gabriel,

- Wi’ books to do ‘im in.

- (From ‘Well?’ In ‘The Unutterable Beauty’, poems by Woodbine Willie/Rev G. Student Kennedy, army chaplain in the First World War).

Hell in the world’s religions

Hell is everywhere: Christianity, Islam, Hinduism and Buddhism. Here are some descriptions:

Christianity: “An ever-burning Gehenna will burn up the condemned… Souls with their bodies will be reserved in infinite tortures of suffering.” (St Cyprian, Letter to Demetrius 24, c.250 AD)

Islam: “Those who deny (their Lord), for them will be cut out a garment of fire. Over their heads will be poured out boiling water. With it will be scalded what is within their bodies, as well as (their) skins.” (Qur’an 22:19-22).

Hinduism: Naraka or Yamaloka are the two main names for hell where sinners are tormented after death. There are twenty eight separate hells for different sins. For instance, in some descriptions Vahnijawa is the hell of fiery flames reserved for potters, hunters and shepherds. The classic belief about re-incarnation is that one gets another shot at Nirvana when a new aeon. That could mean waiting for 4.32 billion years.

Buddhism. Buddhist teaching is that one is born into a Naraka or hell, a freezing one or a fiery one, as a result of one’s accumulated actions. One remains there for hundreds of millions of years.

Judaism. Liberal Judaism has no teaching about the afterlife. The promise of the future relies on one’s physical descendants and on the life of the community. Orthodox Judaism sees hell or Gehinnom as a waiting room for the purification of souls. Most rabbis teach that one stays there for no more than 12 months.

What do people think?

No one talks about hell or judgement nowadays.. But this does not mean that they have stopped being part of people’s mental furniture entirely. Earlier this week I conducted a small experiment. I asked ten people chosen entirely at random on the underground and at a cafe near Piccadilly Circus if they thought that hell existed. Here are the results:

Yes: 1; Probably: 2; Possibly: 4; No: 3.

Unlike Elon Musk’s ambition to fly to Mars, there is no way that anyone can go on a reconnaissance mission to hell and report back. The best we can do is look at how the idea of hell developed in the Judaeo-Christian tradition.

The Old Testament

For most of the 1200 years or more during which the Hebrew Scriptures arose, there was scarcely any idea of the afterlife. The best they could be guess was a dark underworld where the dead had a grey shadowy existence, if you can call it an existence.

In death there is no remembrance of you;

in Sheol who can give you praise? (Psalm 6.5)

But there was a problem. If God is just and death is the end, what about the manifest unfairness of life?

As for me, my feet had almost stumbled;

my steps had nearly slipped.

For I was envious of the arrogant;

I saw the prosperity of the wicked.

For they have no pain;

their bodies are sound and sleek.

Therefore pride is their necklace;

violence covers them like a garment.

Therefore the people turn and praise them,

and find no fault in them.

And they say, ‘How can God know?

Is there knowledge in the Most High?’

(Psalm 73.2-6, 10)

The book of Job has 40 chapters discussing unmerited suffering, with only a couple of verses, Job 19.25-27, giving any sense of hope that might transcend death.

It’ll be all right on the night

By 325 BC Alexander the Great had conquered the whole of the Middle East. By 312 BC the former Persian empire was a Greek state ruled by a general Seleucus I who founded the Seleucid empire. A hundred and forty years later a new king Antiochus Epiphanes sacked the temple at Jerusalem and tried to eliminate the Jewish religion. This led to a revolt led by the Maccabee family. The sufferings of this time are mentioned in the New Testament Letter to the Hebrews in the chapter about faith: ‘(Some) suffered mocking and flogging, and even chains and imprisonment. They were stoned to death, they were sawn in two, they were killed by the sword; they went about in skins of sheep and goats, destitute, persecuted, tormented— of whom the world was not worthy. They wandered in deserts and mountains, and in caves and holes in the ground.’ (Hebrews 11.36-38)

It surely was not just for God to provide no future for his faithful witnesses and to ignore the crimes of their tormentors. Several writings came about which were treasured by the later Christian church such as 1 Enoch, 4 Ezra, the four books of Maccabees and the Psalms of Solomon. These were either written in Greek, or rapidly translated into Greek. Here are some examples:

2 and 4 Maccabees tells the story of seven brothers who were tortured to death for keeping the Jewish law. As they died two of them said to the king: ‘You accursed wretch, you dismiss us from this present life, but the King of the universe will raise us up to an everlasting renewal of life, because we have died for his laws.’ ‘One cannot but choose to die at the hands of mortals and to cherish the hope God gives of being raised again by him. But for you there will be no resurrection to life!’ (2 Maccabees 7.9, 14, c.120 BC)

‘The destruction of the sinner is for ever, but those who fear the Lord will rise to everlasting life.’ (Psalms of Solomon 3.11-12, c.100 BC)

The fate of the wicked is seen as purely negative, they will not inherit life. 4 Maccabees, written about the same time, has a grimmer ending: ‘Because of your bloodthirstiness towards us, you will deservedly undergo from the divine justice eternal torment by fire.’ (4 Maccabees 9.8, c. 100 BC)

Jewish Opinions

What did Jews believe at the time of Jesus? It depended on who you asked. Josephus in his ‘Antiquities of the Jews’, c. 100 AD, explained the ideas of the various groups.

Sadducees, the Temple hierarchy, did not believe in the persistence of souls after death, nor in penalties or rewards in the underworld.

Pharisees believed that the faithful would be re-embodied at the general resurrection.

Essenes believed in the immortality of the soul.

So Judaism in Jesus’ time embraced the three main options: annihilation, resurrection and immortality. But none of them necessarily included the concept of eternal torment for the wicked.

What was Jesus’ position?

Jesus made his position about the afterlife crystal clear when the Sadducees tried to trip him up. “When they rise from the dead, they neither marry nor are given in marriage, but are like angels in heaven.” (Mark 12.25)

But this was not for everyone. ‘Enter through the narrow gate; for the gate is wide and the road is easy that leads to destruction, and there are many who take it.’ (Matthew 7.13)

So what happens to those who don’t qualify for resurrection to life? ‘If your eye causes you to stumble, tear it out; it is better for you to enter the kingdom of God with one eye than to have two eyes and to be thrown into hell, where their worm never dies, and the fire is never quenched.’ (Mark 9.47)

This could just as well mean destruction rather than torment. The destiny of the wicked is Gehenna, the God-forsaken valley outside Jerusalem which in the past had been a place of child sacrifice. The unquenchable fire was an image of total destruction, clearly painful, but not of everlasting torture. ‘Do not fear those who kill the body but cannot kill the soul; rather fear him who can destroy both soul and body in Gehenna.’ (Matthew 10.28)

Paul saw wrath and anguish waiting for those who do not obey God, but these are strictly limited: ‘Then comes the end, when (Christ) hands over the kingdom to God the Father, after he has destroyed every ruler and every authority and power. For he must reign until he has put all his enemies under his feet. The last enemy to be destroyed is death.’ (1 Corinthians 15.24-26)

The only description of fiery torment comes in Jesus’ parable of the rich man and Lazarus in Luke 16.19-31. The point of the story is not to teach about the afterlife, but to give another warning about money. As Jesus said in the Beatitudes in Luke, “Blessed are you poor, woe to you rich!” (Luke 6.20, 24)

(Note: In the traditional wording of the Apostles’ Creed we say “he descended into hell”. The word in Greek is not Gehenna, the place of punishment, but the neutral word Hades, the abode of the dead).

The Invention of Hell

According to early tradition Jesus at the cross said “Father, forgive them, they do not know what they are doing.” When the first Christian martyr, Stephen, was stoned to death, his last words were, “Lord, do not hold this sin against them.” (Luke 23.34, Acts 7.60).

From the second century on the martyrs were not so forgiving: “You threaten me with a fire that burns for a season, and after a little while is quenched; but you are ignorant of the fire of everlasting punishment that is prepared for the wicked.” (Martyrdom of Polycarp, c. 155 AD)

Bt 400 AD the Church had been fully accepted within the Roman Empire. A popular book of that time, ‘The Apocalypse of Paul’, gave detailed descriptions of heaven and hell. But now hell was full of Christians who had not come up to scratch. Christians who leave church services to engage in idle disputes would stand in a river of boiling fire up to their knees. Slanderers of other Christians would be in it up to their lips. Theologians who write bad theology are enclosed in a deep well with an unbearable stench.

The greatest western theologian, Augustine of Hippo (354 – 430) affirmed that the pains of hell would be proportional to the sins of which they were the punishment. This would come about at the general resurrection at the last judgement. Until that time ‘souls will be kept in hidden places of rest and punishment depending on what each soul deserves.’ (Enchirdion 109)

Lightening the load

It was a popular idea that the prayers of living Christians could help the dead even in the afterlife. Augustine said, “This idea I do not contradict, because possibly it’s true.” He taught that purifying of souls before the final judgment was possible for members of the church but not for those outside. 870 year later the Catholic Church finally accepted the idea: ‘If they die truly repentant in charity before they have made satisfaction by worthy fruits of penance for (sins) committed and omitted, their souls are cleansed after death by purgatorical or purifying punishments. And to relieve punishments of this kind, the offerings of the living faithful are of advantage… (2nd Council of Lyons 1274)

At the Reformation, the Protestant churches abandoned the idea of purgatory: ‘The Romish Doctrine concerning Purgatory, Pardons, Worshipping, and Adoration, as well of Images as of Reliques, and also invocation of Saints, is a fond thing vainly invented, and grounded upon no warranty of Scripture, but rather repugnant to the Word of God.’ (Articles of Religion, Article XXII, 1562)

A more modern approach was taken by Josef Ratzinger, the future Pope Benedict XV!: “Purgatory is not, as Tertullian thought, some kind of supra-worldly concentration camp where man is forced to undergo punishment in a more or less arbitrary fashion. Rather it is the inwardly necessary process of transformation in which a person becomes capable of Christ, capable of God, and thus capable of unity with the whole communion of saints” (Eschatology:Death and Eternal Life, 2007)

The roots of Hell

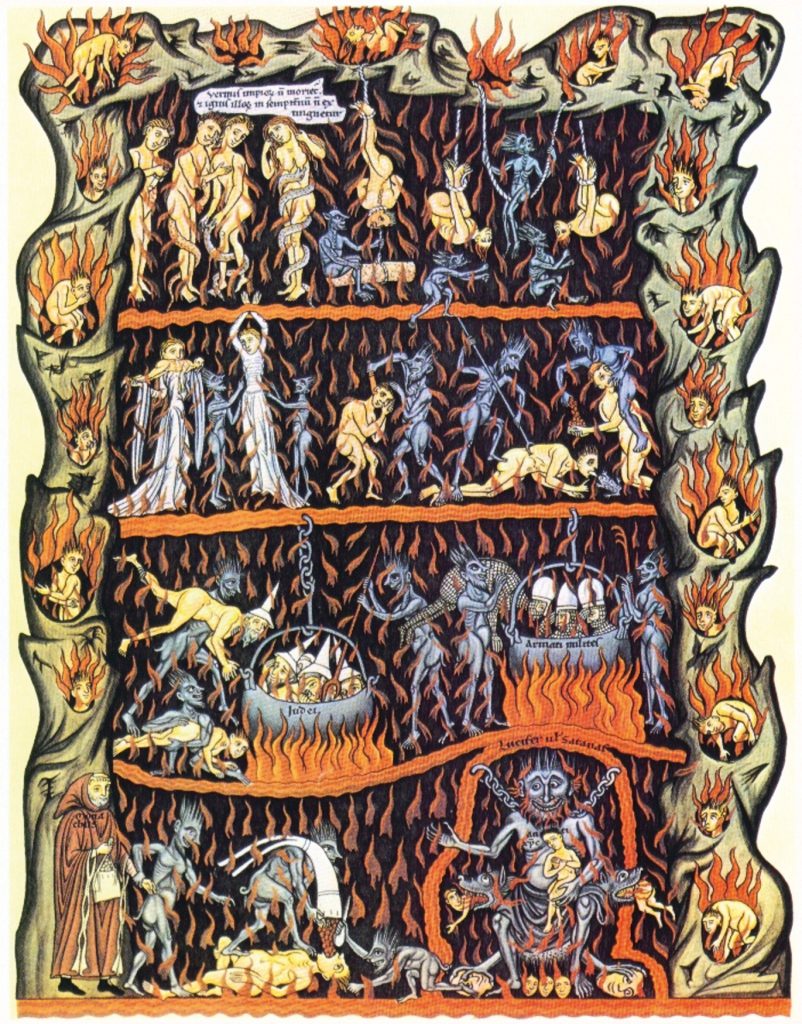

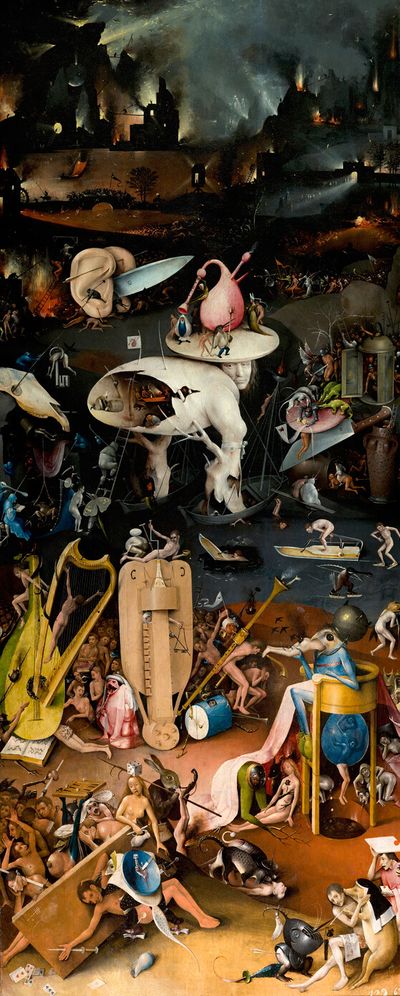

There is something in us that enjoys fear-fulfilment as much as wish-fulfilment. We all enjoy movies about “big planes crashing, big ships sinking, big buildings burning”, to quote the introduction to the film ‘The Big Bus’. Just look at all of today’s dystopian novels. It is not difficult to see why hell has held such a grip on human imagination. All the ‘Doom’ paintings in mediaeval churches as well the (wildly popular) sadistic paintings of Hieronymous Bosch bear witness to this.

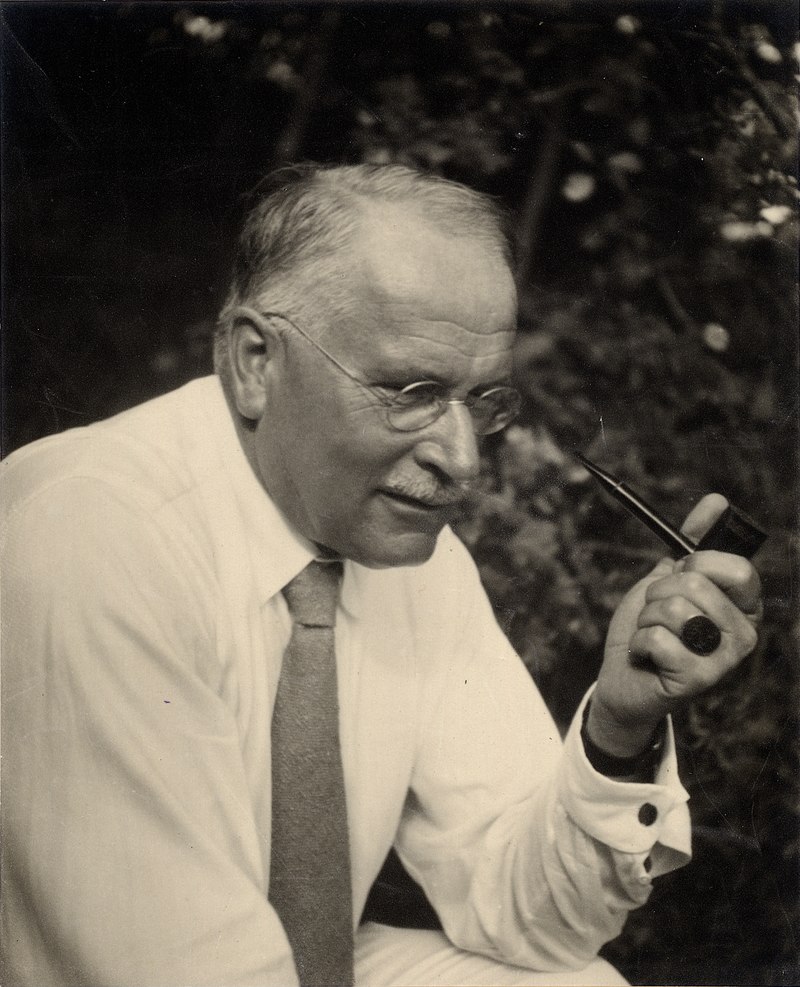

The Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung proposed that underneath our personal consciousness and subconsciousness there is an inherited collective unconscious – universal psychic structures that underlie all human experience and behaviour – with basic thought patterns such as mother, father, child, journey etc. To each ‘good’ archetype there is corresponding shadow archetype. It is through these archetypes that we unconsciously make sense of our lives. If one archetype is a place of blessedness, (the Elysian Fields, heaven etc.) the corresponding shadow archetype is hell, Gehenna, the world after a nuclear catastrophe. It is no surprise that the idea of a place of eternal or quasi-eternal torment should be so long-lasting.

The end of Hell

For the Western world, hell died in the trenches of the First World War. Every year we still pause to remember all those who have died in war, particularly the 744,000 British soldiers who died 1914-1919 out of a total oaf 15 – 22 million. Every year we hear the words: They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old;

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them. (verse 4 of the 1914 poem ‘For the Fallen’ by Laurence Binyon) It is impossible, to suggest that a majority of those young men are even now enduring eternal torments.

Ulrich Simon, like my father, was a German Jew who left Germany for England in 1933. Unlike my father though, he became an Anglican priest and theologian. In 1967 he wrote ‘A Theology of Auschwitz’, reflecting on each stage of the dehumanising process which the Nazis engineered. At the end he considered what was the appropriate end for the perpetrators of this ghastliness. For God to emulate the Nazis by creating effectively an eternal Auschwitz for the wicked was impossible. The only just end for those who created that hell on earth was annihilation.

Jesus seems to have agreed.

Don’t miss next month’s blog: Death etc.

Suggested reading: A History of the Afterlife – Bart Ehrman A Theology of Auschwitz – Ulrich Simon